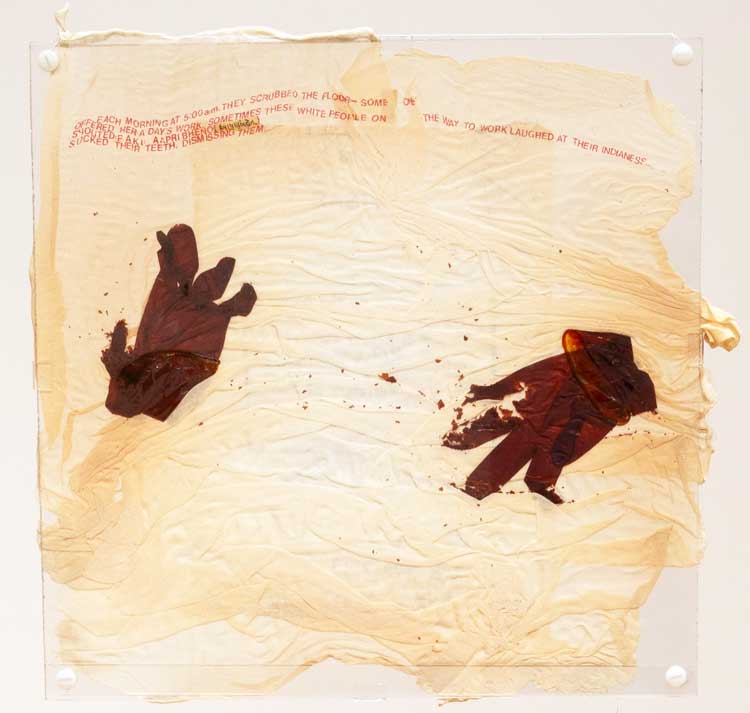

Zarina Bhimji. She Loved to Breathe – Pure Silence, 1987. Courtesy the Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Ruth Clark.

Fruitmarket, Edinburgh

28 October 2023 – 28 January 2024

by BETH WILLIAMSON

There are myriad ways to think about the work of artist Zarina Bhimji. Born in 1963 in Uganda to a family of Indian descent, Bhimji was exiled from Africa in 1974 when she came to Britain. Her frame of reference therefore encompasses three continents and a migratory experience that engages with the postcolonial as well as stretching back to the British empire. It is an unenviable and complex position to be in and one that the artist negotiates in her work with remarkable sensitivity. The writer and critic TJ Demos described one film by Bhimji as “show[ing] itself as redolent of the formidable complexity and depth of history, but where meaning inevitably overflows the gap of documentation and information, and remains open-ended”.1 Her deeply affective practice is deeply political, too, but it is that open-endedness, where meaning itself is something beyond what is seen, that keeps the viewer actively and intensely engaged.

Zarina Bhimji. She Loved to Breathe – Pure Silence, 1987. Courtesy the Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Ruth Clark.

The first work encountered in this exhibition is also the oldest on show, an installation from 1987 called She Loved to Breathe – Pure Silence. Double-sided Perspex frames hang in a line at eye height, suspended from the ceiling. Beneath them, billowing mounds of turmeric and chilli powder (spices used in the cooking Bhimji grew up with) cover the gallery floor. Inside the frames are photographs of everyday objects (jewellery, an embroidered slipper, a dead migratory songbird), printed text from literary sources, a larger-than-life UK Home Office immigration stamp and a pair of, now-perished, surgical gloves.

Zarina Bhimji. She Loved to Breathe – Pure Silence, 1987. Courtesy the Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Ruth Clark.

Nothing quite adds up, but that obliqueness opens up a space where the viewer is invited to consider how people might be overlooked or misjudged. A photograph of jewellery is accompanied by a text: “Slowly she raised her arm, thin dark brown in the sun-haze circled by two heavy gold bangles. This had come from home – every Ismaili girl wore from birth.” So, what might be viewed as ostentatious is, rather, an important connection to family and home. In another frame, the gloves are accompanied by a text that recalls how Indian immigrants doing unpalatable cleaning jobs were subjected to taunts and racial abuse. On the back is an enlarged UK Home Office immigration stamp and now the gloves gesture to the illegal practice of two-finger virginity testing of South Asian women arriving at Heathrow airport in the 1970s “to see whether she was, in fact, a bona fide virgin or fiancee”.2

Alongside this installation from 1987 is the most recent work in the exhibition. Completed just prior to its showing, the film Blind Spot (2023) transfixes for its entirety. In this quietly unfolding work, there is no visual narrative, although an accompanying soundscape lends pace while the voiceover narrative provides a rhythm. Shot in a dilapidated Georgian house, stripped back as if ready for renovation, this empty building is all we see. Bhimji’s visuals, however, are layered with ambient sounds (we can identify the sea and the wind) and music, and a man’s voice tells part of the story, at least.

Zarina Bhimji. Blind Spot, 2023. Courtesy Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Ruth Clark.

The main fictional character, Amina, is a girl of 15 who has been made homeless through family breakdown. We soon realise that the male voice is her social worker, explaining events and the provision of temporary care. His words are neutral and non-judgmental but the slightly staccato rhythm of his delivery echoes the brokenness of the situation – the broken family, the institutional brokenness, the national housing crisis and the broken house before our eyes. This is underlined by the coincidence of a musical crescendo that reaches its zenith as the social worker explains the lack of understanding of ideas of race, class and feminist consciousness in Amina’s temporary home. It is further reinforced by Bhimji’s use of light. She is visually curious and looks at the peeling, broken surfaces to examine how the light plays on them. She thinks of the play of light across the surface as a painterly thing, creating temperature and feeling, as in a Constable landscape. Ultimately, the film does not describe or document, but is instead evocative of Amina’s plight and all the more powerful because of that.

Upstairs, Bhimji’s exemplary handling of light continues in the photograph Shadows and Disturbances (2007), in which the crumbling walls of a palace in Kutch in India take on a beauty that belies their material and condition. In Untitled (A Sketch) of 1999, three children’s dresses are made from maps of India, East Africa and the United Kingdom. In this way, the artist explores identity and subjectivity through the shifting politics and geography of cartography. The work was made as part of her research for the film Out of Blue (2002), which is shown alongside it.

Zarina Bhimji. Out of Blue, 2002. Courtesy Fruitmarket, Edinburgh © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Ruth Clark.

Researched and shot in Uganda, Out of Blue layers images of mist-covered landscape with others of lush green lakes and hills, and a graveyard. Images of empty or temporarily inhabited buildings are devoid of comfort. The fragmented sounds of insects buzzing, gunshots, news reports, anxious human breath and mournful singing come together with the visual images to tell the story of people eliminated and erased. This, like Bhimji’s most recent film, presents a sort of archaeology of place, an interrogation of material memory and, despite the politics, violence and sheer human tragedy implied, these works are almost unbearably beautiful.

Zarina Bhimji. Waiting, 2007. Courtesy Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Ruth Clark.

The exhibition closes with Waiting (2007), a film Bhimji made on being shortlisted for the Turner Prize. Meandering slowly through an empty sisal factory in Kenya, the camera picks out details of the dusty factory – the sisal being turned and spun in the light. Sisal, used for making twine and once a major export for Kenya, was originally introduced under British and German colonial rule. Bhimji was attracted to the material’s hair-like qualities (she mentions barristers’ wigs in the exhibition’s documentary film), but Waiting looks also at the tools and architecture of the spaces while a powerful soundscape includes the buzz and drone of machinery throughout.

Zarina Bhimji. Shadows and disturbances, 2007 (left) and Untitled (A sketch), 1999. Courtesy Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. Collection of the Government Art Collection. © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023. Photo: Ruth Clark.

There is a lot of space in this exhibition and that’s important. The quiet intensity of Bhimji’s work needs that space to breathe, and so do its viewers. The space acts to remove any urgency to move through the exhibition too quickly. Each work needs extended focus and contemplation, the two-dimensional works need close looking, the installations need to be circled around slowly, and each of the films deserves to be watched in its entirely at least once. Bhimji’s cinematic vistas may be beautiful, poetic and atmospheric, but they are also socially and politically charged. At their heart is a condensed consideration of humanity and inhumanity, grief and pleasure, betrayal and love. There is much to learn in this exhibition, and emotions to navigate, perhaps more than can be processed in a single visit. This is an exhibition visitors will want to return to.

References

1. Zarina Bhimji by TJ Demos et al, published by Ridinghouse, 2012, page 12.

2. Virginity tests for immigrants “reflected dark age prejudices” of 1970s Britain, by Alan Travis, the Guardian, 8 May 2011.