by VERONICA SIMPSON

Beyond the gargoyles and saints adorning the pale, 11th-century Caen stone exterior of Canterbury Cathedral this summer, dangling from its cavernous nave hangs a gently luminous installation of glass amphorae, generating the kind of breathless wonder that churches used to instil back when the Sunday service was the week's main entertainment.

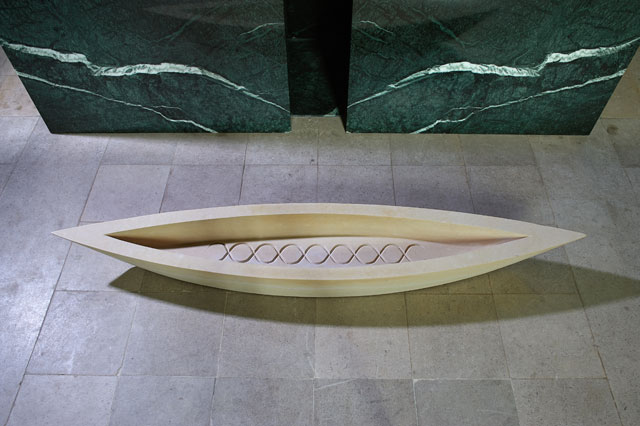

Baldwin & Guggisberg. Boat of Remembrance, 2018 (location: the Nave). Mould-blown glass and steel, blown at Hergiswil, Switzerland. © Christoph Lehmann.

The Boat of Remembrance, by Philip Baldwin (b1947, New York) and Monica Guggisberg (b1955, Bern), features 100 clear, blown-glass vessels that form an elegant boat shape, each vessel intended to represent one of the 100 years since the end of the first world war. With their very emptiness, these amphorae question how we will fill the next 100 years, as well as the extent to which we have forgotten the postwar shifts towards community and equality that have characterised the last century. As Baldwin says: “What’s the point of commemorating the first world war if you don’t embrace the succeeding 100 years?”

Being born in the late 40s and early 50s, respectively, meant Baldwin and Guggisberg’s early years were spent in the shadow of the second world war. This work, The Boat of Remembrance, is the only specifically commemorative work, however. The other nine pieces in the exhibition, titled Under an Equal Sky, are much more preoccupied with the repercussions of those wars and the ensuing moment when the world seemed intent on peace and cooperation, rather than the reinforcement and policing of borders.

Baldwin & Guggisberg. Boat of Remembrance, 2018, detail (location: the Nave). Mould-blown glass and steel, blown at Hergiswil, Switzerland. © Christoph Lehmann.

Baldwin and Guggisberg have lived and worked together for nearly 40 years; they met in Sweden in 1980 while learning to blow glass, and have lived in Switzerland, France and now rural Wales. They call themselves “migratory creatures”, and it is their sensitivity to the currents of tension around the topic of migration that has prompted this exhibition – staged with the help and generosity of a range of sponsors. The cathedral itself provides an extraordinary, layered and resonant setting, as one of the oldest sites of continuous worship in Europe; a daily ritual since the middle ages. It has been a site of pilgrimage (nearly a million pilgrims a year) ever since its former Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, was stabbed here by assassins sent by Henry II. Subsequently sainted, the martyrdom of Becket was the making of this venue, at the core of Canterbury’s Unesco World Heritage Site.

Baldwin & Guggisberg. The Four Assassins, 2018 (location: The Martyrdom). Mould-blown glass, blown at Venini, Murano, Italy. © Christoph Lehmann.

After the spectacular work at the entrance, the other nine pieces activate different points around the vast cathedral complex. For example, The Four Assassins (a work inspired by Becket’s untimely demise), can be found in the Martyrdom, a small chapel dedicated to Becket. Four intensely coloured opaque-glass sentinels (made in Murano, by Venini) lurk in the alcoves of Becket’s tomb, ranging from treacherous green to bloody red.

Baldwin & Guggisberg. The Four Assassins, 2018 (location: The Martyrdom). Mould-blown glass, blown at Venini, Murano, Italy. © Christoph Lehmann.

While their artworks are in the collections of major galleries and museums, it is the design and production of exquisite blown-glass pieces for luxury brands, such as Venini and Rosenthal to Nouvel Studio and Best & Lloyd, for which the duo has been celebrated. However, making art and exploring its ability to provoke new forms and conversations is the area into which they are keenest to expand. This is not their first cathedral – soon after moving to Wales, they were commissioned by Gallery Ten in Edinburgh to create 11 installations for the city’s St Mary’s Cathedral.

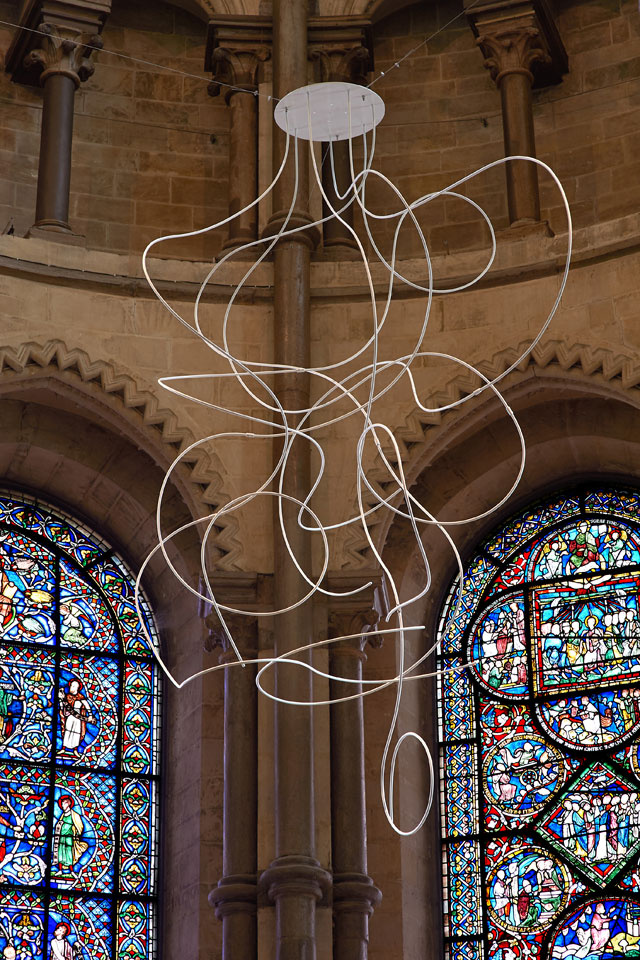

Baldwin & Guggisberg. Unité, Diversité, Egalité, 2018 (location: The Corona). Painted steel. © Christoph Lehmann.

The duo is also keen to expand the media in which they work, and two of the most affecting installations at Canterbury are in metal and stone: Unité, Diversité, Egalité is a sculptural pirouette in white steel, hanging from the Corona gallery, and the Stone Boat, in St Anselm’s chapel, is most eloquent in its simple, elliptical form. It was carved by the cathedral’s resident stonemasons – of whom there are 27 – out of the same Caen stone, from Brittany, from which most of the cathedral was rebuilt under the Norman kings.

Veronica Simpson: Tell me about how this project in this extraordinary setting came about.

Philip Baldwin: It’s an independent project, which has a great many generous donors. It’s a commission in a sense that we agreed to have an element that was commemorative, but it was, on our side, very clear that the show was not a commemorative exhibition. The piece in the nave is in part commemorative. But it’s really a contemporary commemoration. The show is much more about the present and implications for the future that we find when we contemplate the present. Much of what is going on in the present, sadly, had its origins in the first world war. What’s the point of commemorating it if you don’t embrace the succeeding 100 years?

Baldwin & Guggisberg studio view.

With regard to your initial question, we met the dean [the Very Reverend Dr Robert Willis] and prior to installation had made well in excess of 20 trips here, while gradually developing the themes.

Monica Guggisberg: There were obstacles, in terms of learning how to do it technically. From a conservation point of view, certain things need to be respected. On the other hand, all these constraints led to new things – the piece in the nave would not have been possible without the safety deck [in place for other large-scale conservation work]. We would not have been able to hang anything there. When you look at the architecture of the cathedral, certain places lend themselves better for certain things; they invite you.

Baldwin & Guggisberg workshop trialling Canterbury installations.

VS: How did you find your way into the multiple stories, from the first world war to Thomas Becket and more contemporary, news-led issues?

PB: It’s sort of like an onion: there are many layers. We wanted to try and do something that was thematic and embraced these different factors: history, architecture, war, community, culture. The cathedral already represents many of these things. It is a place of sanctuary. Kent is the gateway for refugees and migrants. These things are naturally interwoven.

In addition, Canterbury Cathedral has a theme already in place this year, about migrants and refugees. But migration and refugees are so closely linked to the first world war and its subsequent ramifications that you have a continuum. We need to get that as a culture, and if you don’t get it, we are just going to go on making these appalling mistakes. It looked promising for a while, in the 20th century. However, the exhibition is not intended to be negative. Indeed, just the contrary. And the final piece - The People’s Wall as we call it, in the chapter house - is meant to conclude on a really positive note.

MG: The cultural diversity of our world should be looked at as a wealth, as richness. You can’t go back. The show is about looking forward. And allowing some of the pieces to invite the visitor to have some private reflections and, hopefully, people will be moved by some of it. If just one piece might move somebody, that’s fine.

Baldwin & Guggisberg, glass prepared for Canterbury.

VS: Was there a lot of experimentation for this exhibition?

PB: We had a concept from the get-go. And then it had … tweakings.

MG: We had to make a presentation to the cathedral and the committee was looking at our proposal. There were different pieces. Some of them remain pretty much as we envisaged them; a couple were added. One [Unité, Diversité, Egalité] changed colour completely and became white.

Baldwin & Guggisberg. Pilgrims’ Boat, 2018 (location: Trinity Chapel). Free-blown and cold-worked glass, steel and sand. © Christoph Lehmann.

PB: The steel rods (of this work) are in juxtaposition with The Pilgrims’ Boat, in the trinity chapel. And that, of course, is all about the 300-and-some years when Becket was buried in the chapel. Hundreds of thousands of people came from Europe and actually had to come on their knees. You can see the wear marks of the knees – one of the most powerful architectural elements in the church, these marks around Becket’s then tomb. That boat was meant to represent all that, the pilgrims and diversity. In juxtaposition, you have this steel structure, all in white. It was originally in colours - we tried to pick out all the colours in all the flags in Europe - and then realised it wouldn’t have worked because of the stained-glass windows.

Baldwin & Guggisberg. The Stone Boat, 2018 (location: St Anselm’s Chapel). Kiln-formed glass, steel, used ammunition and related statistics on paper. © Christoph Lehmann.

MG: And, also, it was more powerful to have it in white because all the colours are represented in white. It makes them all equal.

PB: If you spin a colour spectrum, it goes white, which is a nice reference. That concept was there, but it had these evolutions. We only came up with the title about a week ago: Unité, Diversité, Egalité - a bit of a riff on the French.

VS: So, there was a clarity about what you wanted to do because of the spaces and also the ideas you were developing?

PB: We had a great desire to further transcend what we might call our decorative-arts background and expand on that background and move into a more edgy representation. And this context and the fact of commemoration, which is not that important a factor in our view, all helped to percolate these things.

Baldwin & Guggisberg. You, Me and the Rest of Us, 2018 (location: North Aisle). Free-blown and cold-worked glass, gold leaf and steel. © Christoph Lehmann.

VS: The legacy of coloured or stained glass in churches is huge – is that an inspiration or a challenge?

MG: Stained glass doesn’t have any influence on how we work or what we’re doing in this case.

PB: To be very honest, it’s a coincidence, but it’s a nice one. You know, stained glass has been from day one part of the architecture of cathedrals. We happen to work in glass. A corollary of that is the challenge of the architecture generally; stained glass influenced our decision to make that steel-rod piece all white. It was really the only way to go, and it also had a nice twist thematically. But you’re always grappling with the architecture. On the one hand, as an artist, you would say the perfect place is the white cube. But …

MG: I’m not so sure, because if you’re not in a white cube, it forces you to take into consideration the reality that’s around you. The white cube is abstract.

PB: Here, you have a conversation with the surroundings. The boat is in the nave. The amplitude of the boat is relative to the space in the nave. The four assassins are relative to the art of what was possible in the Martyrdom. You could say those are constraints, but they are also positive influences.

MG: We are not religious, but to have this as a stage is very telling – it’s very strong with all the history and all that goes with it.

PB: I have to say, my observation is that the Church of England is very forgiving. They’re quite open. They’re not asking you to be a devoted follower. They take a very “catholic” view. That is part of why the dean was keen to do this. As he himself said very eloquently this morning [at the press launch]: you introduce an artwork into a space, you alter that space for the time that that artwork is in there. You add an element to it that provokes fresh thought, especially for someone who comes regularly. It’s a conversation. And that’s marvellous. It’s an incredible honour to be in this space.

VS: There is also something immersive and captivating about the fragility and intensity of glass that may help in bringing people to a physical space to experience it.

PB: As craftspeople, glass is our primary tool but, as artists, we’d like very much to break out of the glass ghetto.

VS: Working here also meant you had the opportunity to work with the team of stonemasons they have on the staff. What was that like?

PB: An element about the stone boat that was particularly heartening was that it was a way to bring more participation from the cathedral community into this art project. We gave them a blueprint, as it were, and they executed it beautifully. Now it belongs to the cathedral. They gave it to themselves, but it has our signature.

VS: What projects are you working on next?

MG: This project has taken over our lives!

PB: More than anything we’ve ever done. We’ve done bigger projects with museums …

MG: … but with museums they are there to second you. It was a learning curve for us and for the cathedral community as well.

PB: In normal circumstances, you would organise a show like this with at least two other venues. While that is also our ambition with this show, we have been so consumed with the project that we haven’t done anything about it.

MG: The other thing is that it’s difficult to imagine that all 10 pieces could go to another venue. It may be broken up and become part of a different assemblage of pieces.

PB: The Boat of Remembrance is a very powerful object. I cannot imagine it being in another space that would have the drama that it has here.

• Philip Baldwin and Monica Guggisberg’s installation Under an Equal Sky is at Canterbury Cathedral, Kent, until 11 November 2018.