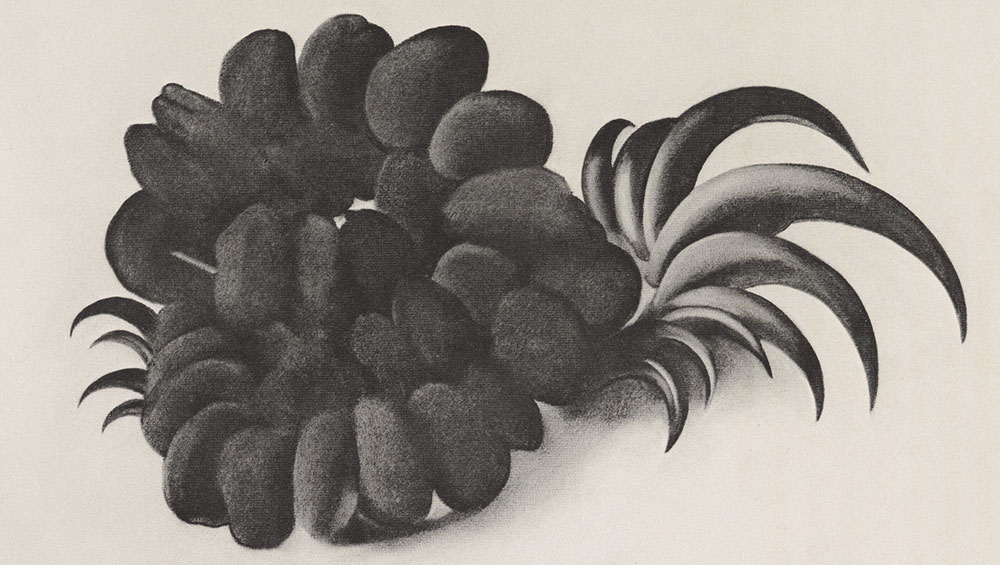

Georgia O'Keeffe, Eagle Claw and Bean Necklace, 1934, from Some Memories of Drawings, 1974. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / DACS, London 2021. Photo: Anna Arca.

Broadway Gallery, Letchworth Garden City

15 June – 23 July 2023

by ANNA McNAY

I realised that I had things in my head not like what I had been taught – not like what I had seen – shapes and ideas so familiar to me that it hadn’t occurred to me to put them down. I decided to stop painting, to put away everything I had done, and to start to say things that were my own.1

It was during the early 1910s that the as-yet-not-well-known artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) began to question what she was doing, what she had been taught, and how perhaps she needed to put all that aside and start afresh in order to be true to and to make something of herself. She decided to focus on the formal elements of a picture – its lines, shapes and tonal values, and to restrict herself to working in black and white until she felt colour to be absolutely necessary. She began to produce a series of mainly abstract charcoal drawings, some of which she would later refer back to as “Specials”, highlighting their significance to her. In career terms, these drawings were not inconsequential, since it was these that caught the eye of the photographer and gallerist – and O’Keeffe’s future husband – Alfred Stieglitz, as well as that of the wider public, when he went on to exhibit them at his gallery in New York in 1916.

The 21 photogravures (etchings with the tone and detail of a photograph through exposure on to a copper plate) of drawings in this Hayward Gallery touring exhibition make up a selection (comprising, in the original, 17 charcoal – nine of which were in the 1916 exhibition – and two pencil drawings, one watercolour and one oil) made by O’Keeffe, together with her agent and close friend Doris Bry, to represent the range of her work in this medium between 1915 and 1963, for publication as two large-format portfolios in 1968. Keen to then enable wider circulation, they went on to publish a limited-edition book of the plates in 1974, which was “moderately priced but very well printed”.2 The drawings were accompanied by texts written by O’Keeffe. This, in turn, was reprinted posthumously, with added biographical notes, intended, Bry states in the blurb, as “a tribute to O’Keeffe’s drawings, an appreciation of her use of the written word, and a proof that a beautifully designed and printed book can be made available to a wide public at an affordable cost”.3 In the exhibition, the prints are accompanied by summaries of O’Keeffe’s texts. (I would nevertheless recommend finding a copy of the book to read these in full, and I am not sure why they were abridged for the display, since most of them are pithy and succinct.) Not only are the works gems in their own right, but, with the pivotal role they played in making the artist we know today, and the disgraceful fact that there is not one single work by O’Keeffe in any UK public collection, this is an exhibition not to be missed.

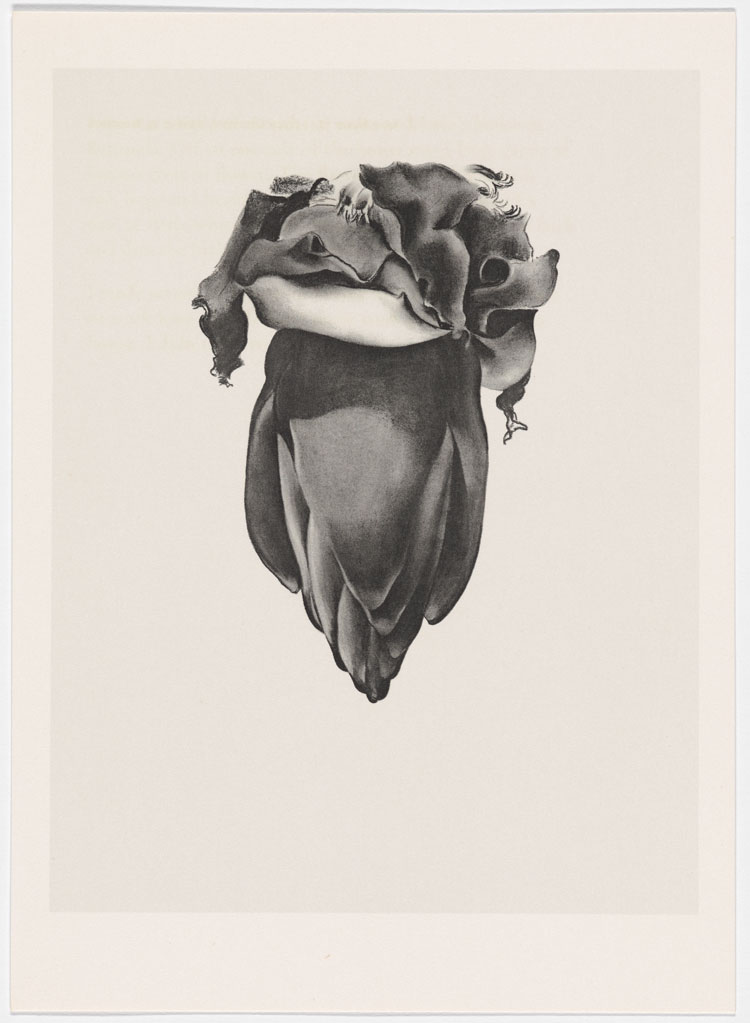

Georgia O'Keeffe, Banana Flower, 1933, from Some Memories of Drawings, 1974. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / DACS, London 2021. Photo: Anna Arca.

This portfolio selection does indeed represent many features of O’Keeffe’s wider oeuvre, both in terms of thematic interests and stylistic approaches, as well as reflecting aspects of her personal life. For example, we see her interest in landscapes – vast open plains and illuminated city skylines; her fascination with bones and shells; her sensual lines and forms (misinterpreted by critics to this day as uncovering deep erotic desire, with Stieglitz having been the first culprit to fuel this fire); her interest in synaesthesia; and, above all, her detailed way of looking at, and breaking down, the subject before her and of coming to understand it fully before attempting to represent it in her work.

The hang, although determined to a large degree by the ordering in the book, diverges only slightly, retaining the rough subgroups (largely according to date). This makes the first encounter in Letchworth that with the most perfectly delicious Abstraction IX (1916). O’Keeffe describes: “I had been walking for a couple of weeks with a girl in the big woods somewhere in the North Carolina mountains. One morning before daylight, as I was combing my hair, I turned and saw her lying there – one arm thrown back, hair a dark mass against the white, the face half turned, the red mouth. It all looked warm with sleep.” She drew this minimalist silhouette of the girl’s head and shoulders first in charcoal, then painted with red, then in charcoal once again. The shape of the head can be made out, only once one has recognised the mouth, which is the sole feature fully depicted, and which, even in its grey tone, stands out as if made up with scarlet lipstick and crying out to be kissed. Around it, a couple of lines capture the sensual sweep of the shoulder, arm and hair, with the faintest suggestion of the girl’s décolleté. Was this solely the dispassionate observation of beauty, or would we be justified in imposing our biographical knowledge – namely that O’Keeffe was bisexual – on to this utterly ravishing image? Whether or not that played a part here cannot be firmly established, but the soft and flowing lines create a sense of longing and desire; the image that emerges is suggested and suggestive. Drawing No 12 (1917), which O’Keeffe simply annotates with “maybe a kiss …”, is again very sensual, evoking symbiosis, two becoming one, the sway of dancing, of being swept up and away. I realise this is anachronistic, but the form(s) in this drawing map(s) almost exactly on to the prime promotional image for the 1987 film Dirty Dancing – Johnny and Baby standing, feet apart, arms entwined, his head bent down to her, hers looking up to him – the epitome of steamy passion for an entire generation.

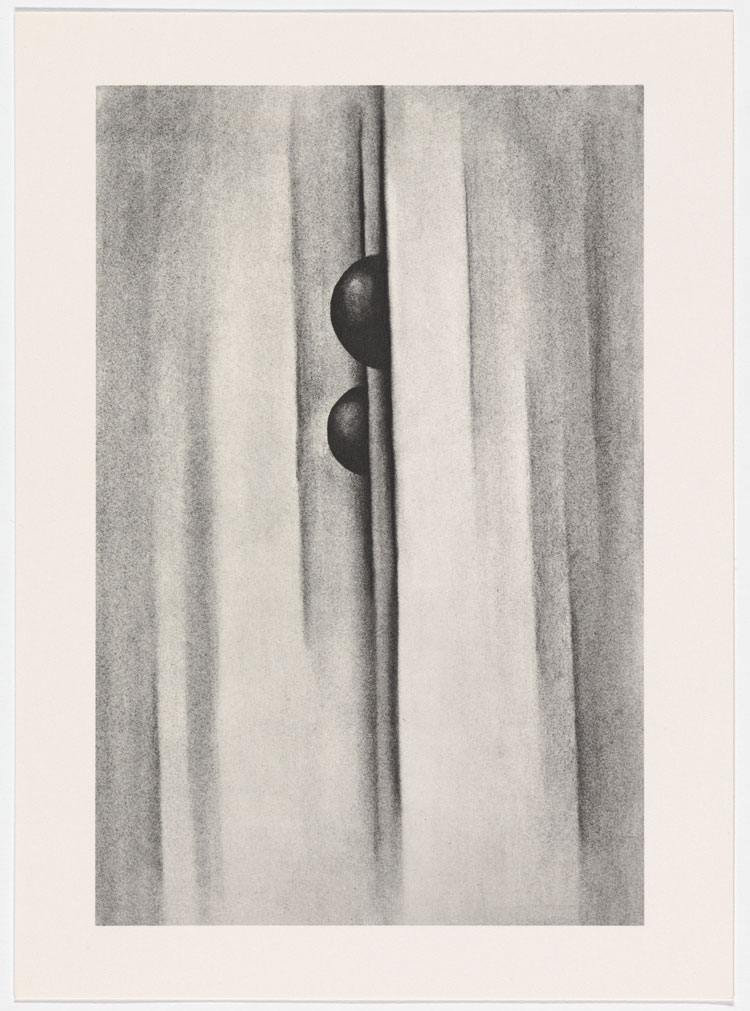

Georgia O'Keeffe, Drawing No. 17, 1919, from Some Memories of Drawings, 1974. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / DACS, London 2021. Photo: Anna Arca.

Drawing No 13 (1915) and Drawing No 15 (1916) were both made after the “perilous climbs” O’Keeffe undertook with her sister, Claudia, at the Palo Duro Canyon in Texas. Of the latter, she writes: “The fright of the day was still with me in the night, and I would often dream that the foot of my bed rose straight up into the air – then just as it was about to fall I would wake up.” Interestingly, O’Keeffe went on to make a painting from this drawing. Despite a near-identical composition, its overall effect is entirely different. In the charcoal, the plateau of the canyon takes on a womb-like quality, with the circular forms roughly evoking the brush scrub common to the area, and the clouds above tessellating like “paving slabs” (cf also her later paintings of clouds in this manner, seen from above through an aeroplane window, such as Sky Above Clouds IV, 19654). The painting (not in the exhibition), however, which bears the title Special No 21 (Palo Duro Canyon) (1916-17), uses bright reds, oranges and yellows, which, contrary to the safety suggested by the charcoal, conjure up the heat of the land (exaggerated to evoke the bubbling magma of a volcano) and the danger of the climb – almost to the point that, if falling, one would fall into the fires of hell. Of course, this vast open landscape, with its slits and clefts, is a prelude to that surrounding O’Keeffe’s final home, Ghost Ranch, in her adopted heartland, on the far-eastern end of the Colorado Plateau, in the New Mexican Rio Arriba County (see later paintings such as Dark Abstraction, 1924).

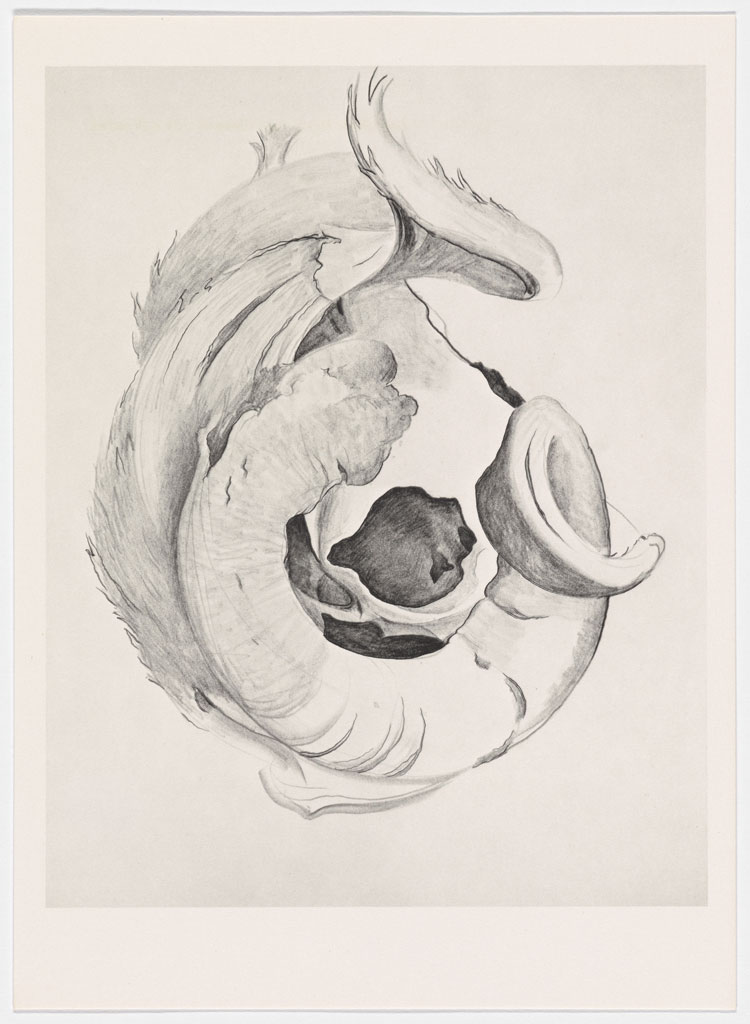

Georgia O'Keeffe, Goat's Horns II, 1945, from Some Memories of Drawings, 1974. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / DACS, London 2021. Photo: Anna Arca.

During her first year living in New Mexico, O’Keeffe began to take home animal skulls and bones that she found on her walks, commenting that she did so because there were no flowers to collect. “The bones are as beautiful as anything I know,” she wrote to her friend, the fellow artist Arthur Dove,5 and her delicate drawings of goat’s, ram’s and antelope’s horns testify to this. Of Drawing No 40 (1934), one of the two pencil sketches included in the portfolio, she writes: “This is from the sea – a shell – and paintings followed. Maybe not as good as this drawing.” The picture is scarcely visible, barely there. The soft and subtle undulations flow like milk poured from a jug, echoing the sensuality of Abstraction IX and Drawing No 12. The curves appear almost to trace the outline of a female form. “Stones, bones, clouds – experience gives me shapes,” O’Keeffe said. “But sometimes the shapes I paint end up having no resemblance to the actual experience.”6 This particular work, she admitted, was a favourite.

At the other extreme (in terms of empty deserts v overcrowded cities), another “landscape” in the portfolio is The City (New York Rooftops) (1930s). Yet, in terms of how O’Keeffe looks at the view and breaks it down into component shapes, it is not that different from the vast emptiness of the desert, or even the magnified petals of a flower. The result, while absolutely recognisable, is a jigsaw of light and dark greys, almost cubist in its abstracted form. One might also see the influence of art nouveau and the arts and crafts movement in earlier works such as Drawing No 9 (1915), which, despite its flowing lines and organic beauty, visualises the throbbing pain of a headache. Drawing (1917?), from a couple of years later, also takes what is happening inside O’Keeffe’s head as its subject matter, although less physically so, as the artist’s accompanying text speaks of “wandering around in one’s thoughts and half-thoughts”. The image of folded blankets or drapes – the darker, heavier material weighing down on the lighter, striped one – evokes the (once again anachronistic) Deleuzian concept of the world as a body of infinite folds that weave through compressed time and space,7 here consuming and claustrophobic, oppressive and without escape.

-Georgia-O_Keeffe-Museum_DACS,-London-2021-Photo-Anna-Arca.jpg)

Georgia O'Keeffe, Ram's Horns II, c.1949, from Some Memories of Drawings, 1974. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum/DACS, London 2021. Photo: Anna Arca.

The flow and folds, softness and fluidity of O’Keeffe’s drawings, and, most essentially, the way in which she analyses everything down to its most basic forms, whereby shells and bones are made up of the same cursive sweeps and strokes as bodies and mountains, epitomise the oft-cited line from William Blake’s poem Auguries of Innocence (c1803): “To see a World in a Grain of Sand”. The clearest examples of this in the portfolio are Drawing I and Drawing III (both 1959), which depict rivers as seen from above, in an aeroplane. Both are charcoal in the original, but have the appearance of watercolour, especially Drawing III, where the distributaries trickle mesmerically into oblivion. Having experienced the modern marvel of flight in 1941, O’Keeffe wrote to a friend: “It is breathtaking as one rises up over the world … and looks down at it stretching away and away … rivers – ridges – washes – roads – fields – water holes – wet and dry … The world all simplified and beautiful and clear-cut in patterns.”8 Even as early as 1916, however, shortly after she turned to the discipline of making these black-and-white drawings, O’Keeffe, on seeing the Texas Panhandle, had written excitedly to Stieglitz: “The plains – the wonderful great big sky – makes me want to breathe so deep that I’ll break – There is so much of it – I want to get outside of it all – I would if I could – even if it killed me.”9 This desire to “get outside of it all”, no matter the cost, to see things “simplified and beautiful and clear-cut in patterns”, is so wonderfully borne out by these rivers and rivulets, which spread across the stark, white page like the branches of a tree, or, scaling down still further, like pulsing veins and arteries. On the walls of this exhibition, an extra layer is added to this perspectival play, as, when I move closer to study these pictures, my shadow looms large, superimposed on the images. Another monotone rendering of something infinitely complex, flattened out and abstracted to a single form in nothingness, or, indeed, “simplified and beautiful and clear-cut in patterns”, my shadow inverts hierarchies, appearing much larger than the rivers; I, the viewer, am now looking down, absorbing, enfolding – entirely from “outside of it all”.

O’Keeffe writes of her study and practising of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, albeit with her conclusion that she would never obtain the fluency of “the Orientals”. Blue Lines (1916), the only work in colour (albeit one single colour) in the portfolio, was done first with charcoal, then black watercolour, before the artist allowed herself to introduce a colour, because “it felt right”. Alongside calligraphy, she had also learned about the Japanese concept of notan – the interplay between elements of light and dark tonal contrast – in a drawing class she had taken with her sisters, and she had read Wassily Kandinsky’s The Art of Spiritual Harmony (1914), where she learned about the concept of synaesthesia (whereby the stimulation of one sense triggers a sensation in another). This awoke in her the connections she had felt between art and music as a child, which she had set aside, when forced to choose between the two disciplines. In December 1915, O’Keeffe spent time stargazing and playing the violin, and, in between times, she made charcoal drawings employing a grab-fisted movement of the whole arm. Drawing No 14 (1916) was one of the outcomes, and, in among its dark bass bands, bouncing tenor squares, and bubbling soprano liquid, she delves into the concept of synaesthesia, exploring “an idea that I was very interested to follow – the idea of lines like sounds”.

The final work in the exhibition again has a calligraphic feel to it, and, along with Blue Lines, is the only one made, in its original, from paint (that one is watercolour, this one is oil on canvas). Titled The Winter Road (1963), the drawing comes from a photograph she took, rendered here in a single sweep of the brush, curving, curling like a ribbon, creating differing thicknesses, intensities and tone. This is a perfect culmination of the show, since it could perhaps also be interpreted as illustrating the trajectory of life, ultimately petering out into near nothingness. There is no colour in this drawing, but it is full of movement and music; to riff on Paul Klee, O’Keeffe seems to be “taking a line for a dance”, tracing the shapes seen in the movement of performers such as Loïe Fuller and Isadora Duncan. And while similar paintings, such as Road Past the View (1964), might also be beautiful and atmospheric, the simplicity of the single flourish and single colour in The Winter Road says as much, if not more.

Stieglitz, on first seeing O’Keeffe’s drawings, described them as: “The purest, finest, sincerest things that have entered 291 [his gallery] in a long while,” going on to say: “Why they’re genuinely fine things – you say a woman did these – She’s an unusual woman – She’s broad minded, she’s bigger than most women, but she’s got the sensitive emotion. I’d know she was a woman – Look at that line.”10 While Stieglitz may have got much wrong about the symbolism of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings (in particular), this brief and immediate reaction to her drawings suggests his instincts were spot on. I can only recommend following his advice: Look at that line.

• The tour of Georgia O’Keeffe: Memories of Drawings will conclude at the Arc, Winchester, 26 August – 15 November 2023.

References

1. Unless otherwise stated, all direct quotes from O’Keeffe are taken from her text (which is without page numbers) in Some Memories of Drawings by Georgia O’Keeffe, The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1988.

2. Publisher’s Note by Doris Bry, in Some Memories of Drawings by Georgia O’Keeffe, The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1988.

3. Blurb, Some Memories of Drawings by Georgia O’Keeffe, The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1988.

4. Georgia O’Keeffe at Home by Alicia Inez Guzmán, Frances Lincoln, London, 2017, page 35.

5. Letter to Arthur Dove, September 1942, cited in Georgia O’Keeffe by Hannah Johnston, Tate Introductions, Tate Publishing, London, 2016, page 20.

6. Georgia O’Keeffe at Ghost Ranch. A Photo-Essay by John Loengard, te Neues Publishing Company, New York, 1998, page 21.

7. The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque by Gilles Deleuze, University of Minnesota Press, 1992.

8. Letter to Maria Chabot, November 1941, cited in Georgia O’Keeffe by Hannah Johnston, Tate Introductions, Tate Publishing, London, 2016, page 25.

9. Letter to Alfred Stieglitz, 3 September 1916, cited in Georgia O’Keeffe by Hannah Johnston, Tate Introductions, Tate Publishing, London, 2016, pages 8-9.

10. Alfred Stieglitz, on seeing O’Keeffe’s drawings, as reported by close friend Anita Pollitzer in a letter to O’Keeffe on 1 January 1916, cited in Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. Two Lives. A Conversation in Paintings and Photographs by Elizabeth Turner, Belinda Rathbone, and Roger Shattuck, Callaway Editions, New York, 1992, pages 80-81.