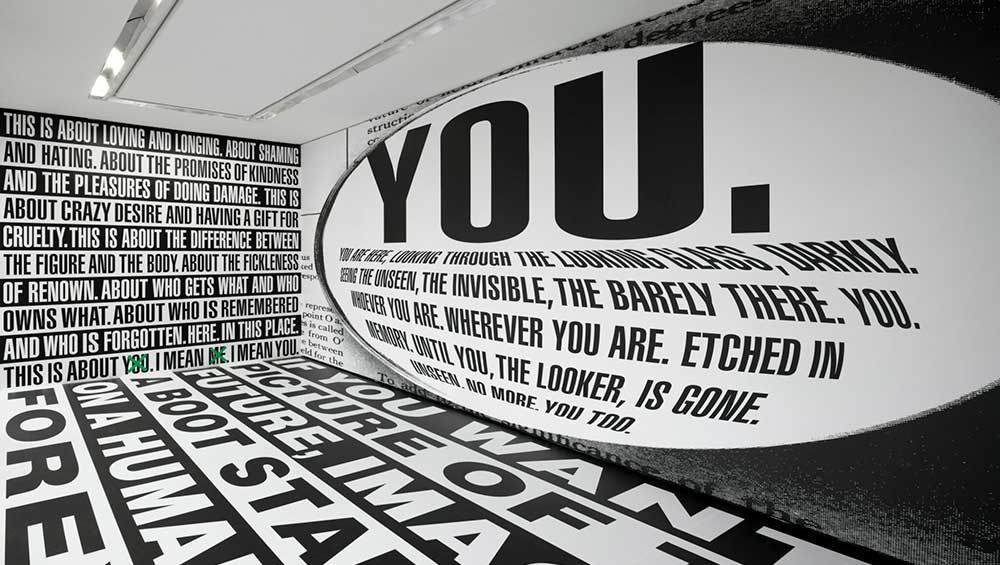

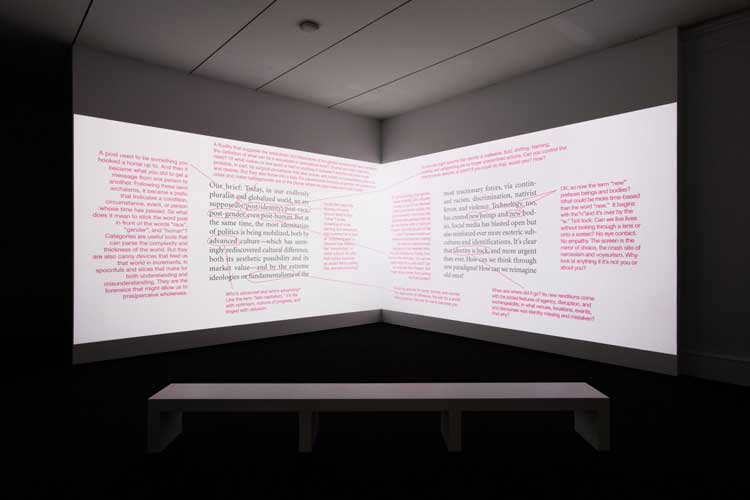

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Installation view, 1 February – 17 March 2024, Serpentine South. Photo: George Darrell.

Serpentine South, London

1 February – 17 March 2024

by ANNA McNAY

I admit to never having paid much attention to Barbara Kruger (b1945, Newark, New Jersey, US) before visiting this exhibition, which certainly speaks for the fact that I had only encountered her works in passing in books. In the flesh – or certainly, insofar as my experience now extends, in the gallery context – they cannot be ignored, shouting loudly, concisely and powerfully in their tabloid black, white and red sans serif typeface (Kruger uses mainly Futura Bold, with the occasional foray into Futura Bold Oblique or Helvetica Ultra Compressed). A longstanding fan of Jenny Holzer, I mistakenly thought I had Kruger “covered”. While, yes, they may be considered under the same umbrella as female American conceptual artists who use typography as a major component of their work, and, as Kruger says, who “share an understanding of how power circulates through culture, how it bestows on some and withholds from others”,1 there is far more finesse to each of their oeuvres than this simple reductionism allows for. Kruger’s work, it turns out, is as poetic as it is urgent, and her statements – more often than not, in fact, questions – while speaking for and to the many, are nevertheless the product of her uniquely personal trajectory and experience.

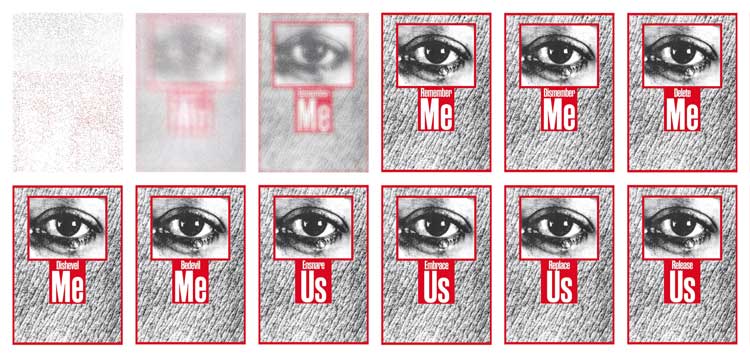

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Remember me), 1988/2020 (stills). Single-channel video on LED panel, sound, 23 sec. 350.1 × 250.1 cm (137 7/8 × 98 1/2 in). Courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers.

Kruger’s “education” comes from lived experience rather than from academia. She attended Syracuse University, but left after a year when her father died. She then studied for one term at the Parsons School of Design in New York, but again dropped out so that she could work and earn some money. She was lucky, in as much as she landed a design job at Condé Nast publications while still in her teens, and she soon graduated to the position of head designer. She also wrote film, television and music columns for the likes of Artforum. She describes laying out the page, without having the copy, and therefore just placing dummy text. This combining of word and image, and her baptism into the cult of contemporary culture, soon morphed into a career as an artist – “On a formal level of cropping imagery my experience in magazine design makes up 85% of my work”2 – initially producing small (28 x 33cm) monochrome pieces known as “paste-ups”, with the key difference from her design work being the creation of meaning. These paste-ups went on to be reappropriated in larger collages, as “wraps” (wallpapering rooms, buildings and public transport), and in digital form (as “re-plays”). Examples of all these variants are included in the current exhibition at Serpentine South, London.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Installation view, 1 February – 17 March 2024, Serpentine South. Photo: George Darrell.

From the instant you enter the gallery, you are in some alternate reality, shrunken, like Alice, and drawn into a world of ginormous greyscale hands, reaching down towards you, proffering sim-card-like collages, littered with statements (“You should never have to apologise for the way you need to be loved”), accusations (“Not punk enough, not pop enough”, “Not pretty enough”), assertions (“I’m not your bitch”), questions (“I know you are, but what am I?”), predictions (“You’ll always be poor”) and profound insights (“I Instagram, therefore I am”, “Our world is much more complex than a Rubik’s”) (Untitled (That’s The Way We Do It), 2011/2020).

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Installation view, 1 February – 17 March 2024, Serpentine South. Photo: George Darrell.

I wonder whether I might have been short-circuited inside the pre-frontal cortex of my brain, as language and imagery, bombarding me from all sides, come together seeking unity in categorisation. Utterances composed of individual words, are collaged and montaged, like fridge-magnet poetry, on to black-and-white found imagery, sometimes congruently, sometimes not. It is hard to say what the eye is drawn to first, or whether that is necessarily the order of processing. It is all so incredibly heady. This is a direct embodiment of Kruger’s – and our – realisation that: “Seeing is no longer believing. The very notion of truth has been put into crisis. In a world bloated with images, we are finally learning that photographs do indeed lie.”3

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Installation view, 1 February – 17 March 2024, Serpentine South. Photo: George Darrell.

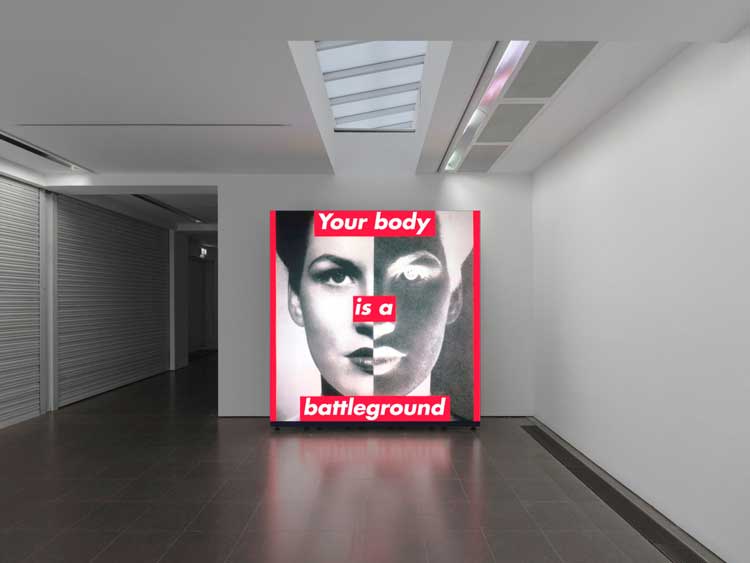

Then there is the audio aspect: heavy clicks, like an old-school cash machine, or hitting return on a typewriter, which, as I acclimatise, I realise accompany the alternative phrases, being “rung up” in the digitised re-plays of some of Kruger’s most seminal works – sometimes word salad, frequently absurd, and yet nearly always, in the absence of time to overthink them, strikingly profound. They speak the truth, in their sensationalism, not only of the page-three model, but of the student, the professor, the nurse, the mother, the daughter, the sister, the hysteric and her psychiatrist. Take, for example, Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) (1989/2019), one of the best-known “Krugerisms” there is. It was originally created as a poster for the Women’s March on Washington in 1989, in support of abortion rights, as established in 1973 with Roe v Wade. It has since – among other things – been reused as a Berlin subway poster; a billboard commissioned by the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio; in Poland, in protest against restrictive new abortion laws; in various mutations as magazine covers and op-ed pieces; and, in 2022, with the wording “Who becomes a ‘murderer’ in post-Roe America?”, as a New York Times magazine cover, in the lead up to the supreme court’s overturning of this legislation. For Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, Kruger has created a re-play version comprising animated puzzle pieces with “new associations for the 21st century”. YOUR BODY IS A BATTLEGROUND becomes, among other things: YOUR WILL IS BOUGHT AND SOLD, MY BODY IS MONEY, YOUR HUMILITY IS BULLSHIT and YOUR SKIN IS SLICED.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Installation view, 1 February – 17 March 2024, Serpentine South. Photo: George Darrell.

Other works speak their thoughts aloud, but I scarcely notice this soundtrack until prompted by an accompanying non-verbal intrusion, or the loud swooshing away of text, which, dizzying in its rapid oscillations, makes me question whether the exhibition might not have benefited from a strobe-light-esque trigger warning. Kruger describes these sonic interventions as “rogue audio” and “just another way of challenging and adding to receivership.”4

I could easily have sat through multiple loops of each collated video piece, so in thrall was I to the rambunctious words. I especially enjoyed Pledge, Will, Vow (1988/2020), comprising variations on the traditional marriage vows, the last will and testament and the US Pledge of Allegiance. As the text of each oath is typed, white on red, there is a pause at key words, which “[l]ike all words, [are] up for grabs”5, as they flick through a series of potentially alternative synonyms. “Allegiance”, for example, cycles through “adherence”, “adoration”, “anxiety” and “affluenza”, while “sickness” becomes “contagion”, “exhaustion”, “neurosis” and “addiction”. In Remote Control, a collection of her criticism, Kruger asks: “How does one describe this inclusive ceremony of benevolence without folding into doltish self-parody?” and, quite brilliantly: “How does one speak of democracy without collapsing into a treacly puddle?”6

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Installation view, 1 February – 17 March 2024, Serpentine South. Photo: George Darrell.

Untitled (No Comment) (2020), having its London premiere in this exhibition (iterations of which have already taken place at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, New York), is a true pièce de résistance. An immersive, three-channel video installation combining text, audio and a barrage of found images and memes, it includes footage from TikTok and Instagram (despite Kruger admitting she is but “a reader”, “a follower” and “a lurker”, without accounts of her own) alongside quotes from such extremely different sources as the French Enlightenment philosopher and writer Voltaire and the millennial American rapper Kendrick Lamar. Kruger presents all her works as accessible yet meaningful, a commentary on how we consume information and visual culture today, and this, her first video inspired almost wholly by time spent online, is a case in point. Of course, there is also her unsettling trademark undercurrent questioning power relations: how these are created, expressed and experienced. An especially impactful section of the film comprises the typing of a letter, laying bare the recipient’s abuse of the author, but with a heavy strike-through redacting as quickly as the original sentences appear, frighteningly rendering the remaining text a love letter full of praise.

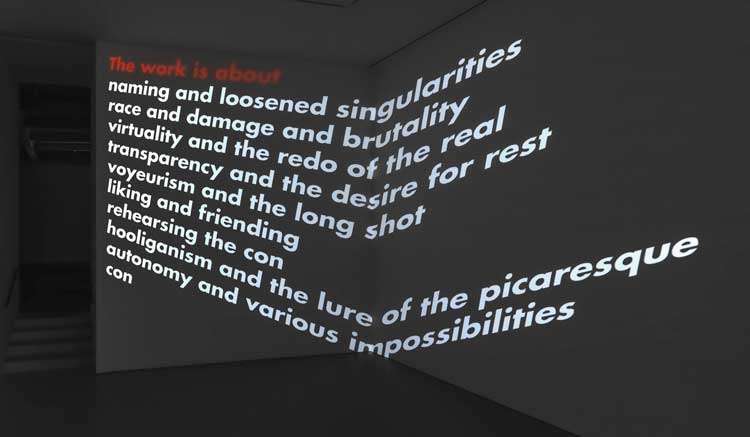

Barbara Kruger Untitled (No Comment), 2020 Three-channel video installation, colour, sound, 9 min. 25 sec. Installation view, Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. Installation view, 1 February – 17 March 2024, Serpentine South. Photo: George Darrell.

As for the lip-syncing Persian blue and motley crew of other moggies in Untitled (No Comment), Kruger says: “Of course there’s a cat, the star! For years, I’ve been so entranced by cuteness and its place online. An online rife with porno, conspiracies, violence, clout, influence and cuteness. Early on, I would Google ‘kitty in toilet bowl’ – and sure enough there it is!”7 What was especially amusing, as I sat watching this film, was the woman next to me, who, each time a cat appeared, would whisk her smartphone up from her lap and attempt to photograph it; every time, however, she was nanoseconds too slow, as the feline disappeared in the blink of an eye. With regard to this rapid reel, Kruger says: “We live in the age of the soundbite where the attention span of the average viewer is for ever shrinking. I want to engage that attention span and allow my work to speak out to audiences that remain secluded from the privileged terrain of the art world.”8

It is Kruger’s use of “direct address”, in particular through the incorporation of pronouns – primarily “you” and “we” – that implicates the audience in the specific scenario being sketched. “We” acts as a springboard between the personal and the impersonal, since, as Kruger’s friend, Craig Owens, for whom she designed a book, notes (himself citing the French linguist Émile Benveniste): “‘We’ does not signify a ‘multiplication of identical objects, but a junction between the ‘I’ and the ‘not-I’.”9 Kruger reflects: “It really cuts through the grease to use a pronoun. You know, you’re literally reaching out and touching someone on a certain level.”10

Nowhere does this use of pronouns have greater effect than in Untitled (Forever) (2017), a “wrap” work of black-on-white text, completely wallpapering the gallery’s education space. The word “YOU.” (introducing an excerpt from a speech by Virginia Woolf) virtually fills a whole wall, printed as if on a convex shape, the added full stop packing a weighty punch. You? Who, me? What have I done (or not done)? As the art historian and curator Zoé Whitley observes: “By playing with perspective anamorphosis within the cartouche inscription, Kruger holds up a distorted mirror into which we peer, one that acknowledges the gawking subject only to dismiss and disregard that person.”11 The viewer is nowhere a more active participant, required to use their agency and move around the room in order to fully apprehend the (fairly brutal) messages. Another effect of the anamorphosis is that it is the texts in our peripheral vision – those we perhaps cannot quite fully grasp – that taunt us the most. The text on the floor is taken from George Orwell’s 1984, a text Kruger has used in numerous other works as well, and reads: “IF YOU WANT A PICTURE OF THE FUTURE, IMAGINE A BOOT STAMPING ON A HUMAN FACE – FOREVER.” This concept triggered a form of internal echolalia and has been hauntingly – or, indeed, tauntingly – playing on repeat in my head ever since. Whether this is an attempt to process, in response to fear, or for some other reason entirely, I cannot say, but it spawns an exceptionally uncomfortable feeling – doubtlessly just as intended by Kruger and Orwell.

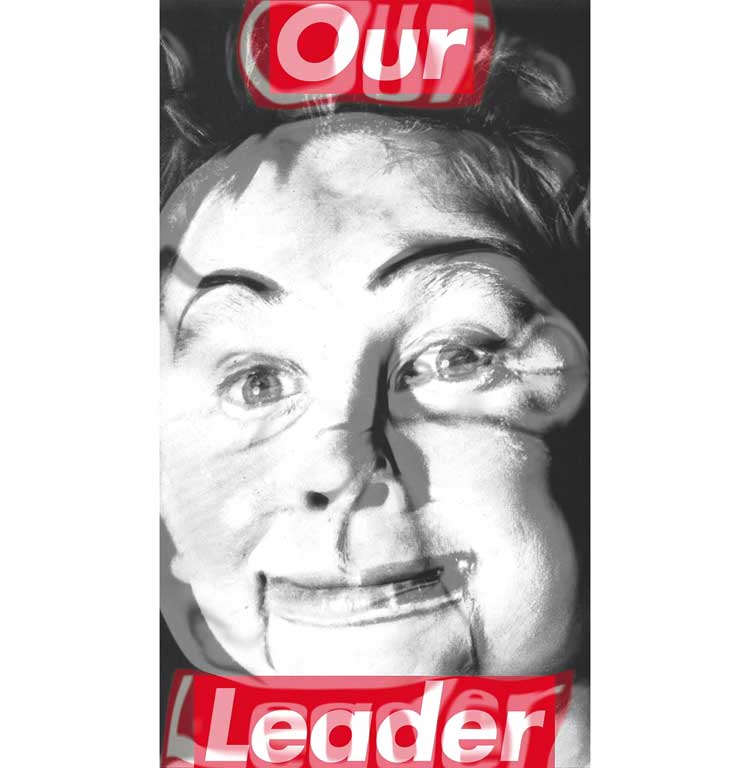

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Our Leader), 1987/2020. Single-channel video on LED panel, sound, 24 sec, 350.1 × 200.1 cm (137 7/8 × 78 3/4 in). Courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers.

Knocking us from the safety of our comfort zones, Kruger “expands the frame for the existence of liminal spaces between self-doubt and self-belief, superiority and oppression, fiction and reality.”12 As someone who lives with a loud, chaotic and overfilled mind, Kruger’s verbal and visual splurges appeal to me greatly. They are – as she says of the everyday – somehow comforting (although I appreciate this might not be the case for those with naturally quieter minds); they acknowledge the overwhelm of how it feels to be a part of today’s nonstop, high-speed world. I recently heard someone describe their litmus test for whether someone likes a piece of art or not as whether they would hang it in their downstairs toilet (presumably so as to be on show to visitors?). Well, I would wallpaper not just my downstairs toilet (were I to have one!), but, quite honestly, my entire flat with these collages, and that is saying something (not least since art is usually on the losing side of the competition with books and shelving when it comes to wall space). Kruger’s polemic aphorisms are not so much values to live by as interpolations to make you stop and check yourself and your actions: “The viewer must choose where to stand between hierarchies of speaking up and hero worship.”13 The art historian Miwon Kwon further notes that Kruger “radically explode[s] the viewer’s habituated complacency”.14 It seems only fitting, however, to leave the final word to Kruger, who sums up: “I never consider myself to be the grand commentator, the one with the answers, the ‘moral’ one. I’m more interested in questioning the surety of knowledge and a conception of ‘morality’ that has become the alibi for so much unrelenting terror and abuse in this world.”15 Kruger’s work has penetrated my mind, and I both fear and celebrate the fact that I will never see things the same way again. Such is the power of Kruger’s art.

References

1. Barbara Kruger: ‘Thank God I’m an artist and not a movie or Tiktok star’ by Jori Finkel, The Art Newspaper, 16 August 2021.

2. From the Archive: Being Barbara Kruger by Mark Sanders, AnOther Magazine, 22 April 2020.

3. Remote Control. Power, Cultures, and the World of Appearances by Barbara Kruger, MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 1993, page 4.

4. Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, exhibition booklet, Serpentine South, London, 1 February – 17 March 2024.

5. Remote Control. Power, Cultures, and the World of Appearances by Barbara Kruger, MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 1993, page 59.

6. Ibid.

7. Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, exhibition booklet, Serpentine South, London, 1 February – 17 March 2024.

8. From the Archive: Being Barbara Kruger by Mark Sanders, AnOther Magazine, 22 April 2020.

9. Problèmes de linguistique générale by Émile Benveniste, Gallimard, Paris, 1966, volume 1, page 233. Beyond Recognition. Representation, Power, and Culture by Craig Owens, University of California Press, 1994, page 192.

10. Barbara Kruger: In Conversation with Iwona Blazwick, Modern Art Oxford, 27 June 2014.

11. Enough About You. Let’s Talk About Me by Zoé Whitley, 7 November 2022.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. A Message from Barbara Kruger: Empathy Can Change the World by Miwon Kwon. In: Barbara Kruger by Barbara Kruger, Rizzoli, New York, 2010, page 95.

15. From the Archive: Being Barbara Kruger by Mark Sanders, AnOther Magazine, 22 April 2020.

• From 4 March 2024, a digital installation, Barbara Kruger, Silent Writings (2009/2024), will be displayed on selected Monday evenings on the wrap-around public screens situated at the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Charing Cross Road, alongside Centre Point, in collaboration with Outernet Arts.