Saatchi Gallery, London

27 May–16 October 2011

by ANNA McNAY

Martin Honert. Riesen (Giants), 2007. Styrodur, polyurethan-rubber, wool, clothing, leather, 300 x 100 x 80 cm. Courtesy the Saatchi Gallery, London. © Martin Honert, 2011. Photo © Stephen White.

The works draw their audience in, making us a part of the installation, and raising questions about the process of sculpting itself. Peter Buggenhout’s large clumps of dirt, looking as if they’ve been dug up and brought from a building site, are actually carefully sculpted recreations from the artist’s studio. Roger Hiorns’ crystalised cathedrals, at the other end of the same room, however, developed slowly through chemical growth, independent of the artist, who had relinquished control to the materials themselves. On the same floor, we find Folkert de Jong’s decaying tree trunks, Rebecca Warren’s invitingly tactile clay figures, and David Thorpe’s garden growing in the middle of gallery 9.

Roger Hiorns. Copper Sulphate Chartres & Copper Sulphate Notre-Dame, 1996. Card constructions with copper sulphate chemical growth; mounted on glass and wood trestle table with Perspex cover underlit by two strip lights, 137 x 125 x 65 cm. Courtesy the Saatchi Gallery, London. © Folkert de Jong, 2007.

Upstairs we enter a parallel universe of light, from Bruce Dahlem’s blindingly white neon The Milky Way (2007), to Anselm Reyle’s and David Batchelor’s vivid installations in full technicolour, the latter seeking to present a “distillation of colour’s presence in our everyday environment”.

Björn Dahlem. The Milky Way, 2007. Wood, neon lamp, bottle of milk, dimensions variable. Courtesy the Saatchi Gallery, London. © Björn Dahlem, 2007.

In Oscar Tuazon’s Bed (2007–2010), the domestic becomes architectural, and in Martin Honert’s Riesen (2007), a childlike sense of immensity is brought to life in his 2.72 metre high hoody-clad trekkers.

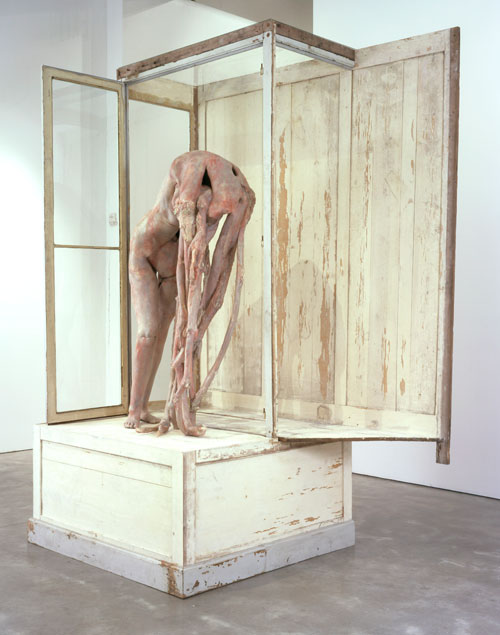

Berlinde De Bruyckere. Marth, 2008. Wax, epoxy, metal, wood and glass, 280 x 172.5 x 119.5 cm. Courtesy the Saatchi Gallery, London. © Berlinde De Bruyckere, 2008.

Whether human or equine, Berlinde de Bruyckere’s sexless, featureless, objectified bodies, mounted on a plinth or encased behind glass, offer a beguiling depiction of suffering, magnified through their piteous anonymity. Thomas Houseago’s crude white figures, likewise hovering between figuration and abstraction, are larger than life, yet, in their cowering poses, evoke a vulnerability, redolent of power and destruction. The plaster and hemp of Figure 1’s (2008) leg is torn back to expose the rusted iron skeleton, revealing its fragility, and echoing the tortured expression. Much the same strategy is at play next door in Dirk Skreber’s car installations, in which seemingly indestructible objects are displayed scratched, bent round poles, and exposed – a shattered creation.

David Altmejd. The Healers, 2008. Wood, foam, plaster, burlap, metal wire, paint, work dimensions 206 x 326 x 326 cm, plinth dimensions 33 x 367 x 367 cm. Courtesy the Saatchi Gallery, London. © David Altmejd, 2008. Photo © Stephen White.

For me, however, the star of the show, is David Altmejd’s The Healers (2008), a massive orgy of plaster: hands, feet, entrails, toes curled in agony or ecstasy, a winged figure orally stimulating the central grey figure, in turn locked in an embrace with another writhing in a lurid pink. The mirrored “step” around the edge of the plinth captures and reflects you, warning, perhaps, that if you venture too close you too will become embroiled. Repulsive yet alluring, baroque yet contemporary, figurative and abstract rolled into one. Judging by the contents of the show as a whole, this is indeed an encapsulation of the shape of things to come.