The exhibition includes works by ten Magnum photographers of different generations, backgrounds and experiences, including Abbas, who was born in 1944 in Iran and has been a Magnum member since 1985; Bruce Gilden, born in 1946 in Brooklyn, New York, and a Magnum member since 2003; Gueorgui Pinkhassov, born in 1952 in Russia and a Magnum member since 1994; Patrick Zachmann, born in 1955 in France and a Magnum member since 1990; and Donovan Wylie, born in 1971 in Belfast and a Magnum member since 1997. Although the chosen photographers represent different trends in documentary photography, they have discovered kindred spirits in Magnum's founders. Cartier-Bresson and his colleagues aspired to the complete independence necessary for photographers to function as artists, from selecting subjects to controlling how images are used, retaining negatives and owning copyright.

The English-language version of the show's title, 'The Image to Come', contains an interesting play on words. Beyond its sense of temporal continuity, 'd'après' denotes a sense of conceptual kinship, and so 'l'image d'après' can also mean 'the image inspired by'. Considered by many as the most talented and influential photographer to date, Cartier-Bresson coined the term 'l'image d'après' to express what he believed was the defining aspect of film, something that set it entirely apart from photography. For him, film was the dynamic image that comes after the static photo, an image full of movement.

For their contributions to this exhibition, the ten photographers attempted to document cinematic universes, but they did not shoot pictures for films, nor did they create works directly inspired by films. Instead, they looked to their previous works for inspiration. It is an inspiration 'd'après' (after) the images, as described by Cartier-Bresson; and it is a kind of archaeology of their own works as a means to discover something new in what is past.

The concept of dual meaning runs throughout the exhibition. Curators Diane Dufour, Magnum special projects director, and Serge Toubiana, general director of the Cinémathèque Française, asked the photographers to choose images from their works which they felt could be considered 'd'après' (both 'after' and 'inspired by') the cinema. While some drew correspondences to a particular film, others connected to a particular filmmaker's style, philosophy and/or imagery. The results of this novel curatorial approach is displayed on the fifth floor of the Cinémathèque's new home, a building designed by Frank O Gehry and opened in 2005.

While visitors view the exhibition, another issue, or undercurrent, will become apparent; one that is, perhaps, too strong to remain in the background. Magnum's members describe the collective as an agency of 'documentary photography'. Over the past 60 years, Magnum has changed the way the world understands 'photojournalism'. Through Magnum's work, the recording of 'real scenes' has become an art.

Magnum's founders hoped to demonstrate the power of photography to capture critical events that represent turning points in history. They wanted to display very personal views within the context of documentary photography. As they achieved their stated goals, they created a new look for photojournalism that has become a standard followed by photographers around the world.

Today, the agency's members number 60; each member retains control over his or her works and has an equal place in the co-operative. Internationally, works by Magnum members are held as examples of visual testimonies made to the highest aesthetic values. By attributing greater importance to the eye, or vision, of the photographer, one could say that Magnum members have redefined the notion of an 'eyewitness'.

As such, this exhibition serves as a vehicle for examining images that 'document' events and conditions and are also works of art. The opposition of two functions creates a tension: The more precisely an image can communicate and transmit a message, the less ambiguous it becomes; the inexpressible and highly individual vision that is essential to a work of art is, somehow, clouded or lost. To bridge the gap between life and art, Magnum members have perceived the complex symbolic field surrounding a documented image, amplifying content, depth and meaning.

The first images on display are by the American Alec Soth, who took for his inspiration German filmmaker Win Wenders. Here, the source is direct: Wenders' 1976 film Kings of the Road. The film tells the story of a projectionist who drives through the German Federal Republic at a time when theatres across the country were closing. Soth is known for capturing the stereotypical modern American lifestyle, revealing a darker and tragically empty side. Recently, he travelled across Texas to photograph abandoned theatres. In fact, Soth shot pictures in Paris, Texas, the small town which served as the title of one of Wenders' most important films.

Moving beyond a coincidence of subject, Soth explored what has become for him an obsession: the road movie. This obsession is the mirror that creates the 'faraway-so-close' effect between Soth's and Wenders' works. Like Wenders, Soth comprehends the road movie genre as a sequence of stops on a long journey. Always, Soth shoots theatre façades with bright, sunny blue-sky backgrounds. He takes pictures perpendicularly, and these images appear to be two-dimensional. His methods create tension between the idea of 'travel' and the stopped images; an effective translation of the road movie universe results.

Next in the line-up, visitors will find an opposite approach taken by the Iranian (resettled in Paris) photographer Abbas, who was inspired by Roberto Rossellini's film Paisà (1946). One of the fathers of the Italian neo-realism movement, Rossellini filmed Paisà, a group of six vignettes following the Allied invasion from July 1943 to winter 1944, from Sicily to Venice, shooting fiction aesthetically as if it were a documentary film. The realistic images shown in Rossellini's film portray the fear, uncertainty, despair and utter disbelief felt by those whose lives were shattered by war.

For his contribution to the exhibit, Abbas offered his 1978/1979 photo-essay on the Iranian Revolution. While in the Wenders/Soth dialogue one can see movement that became stationary, here one is faced with images full of movement. The film and the photographs are in the same black and white documentary-but-fictional style of neo-realism, but Abbas's images are not fictional. By juxtaposing stylistically similar works in mediums with opposing aims, Abbas extends the aesthetic experience of both. A screen showing the film further strengthens the effect. (Screens showing scenes from the film inspirations accompany all exhibited works.)

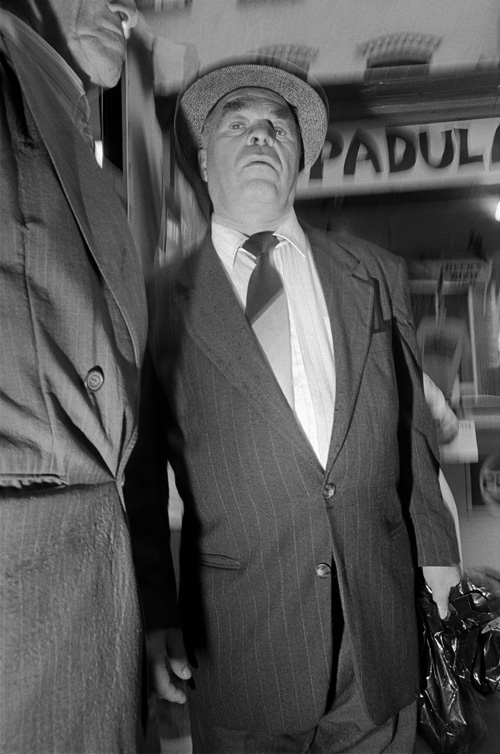

Bruce Gilden's images 'd'après' 1950s American noir films follow. His pictures were shot in New York from 1984 to 2001. These photos showing New Yorkers are in Gilden's elegant black-and-white style with his signature method of playing with focus. As viewers take in Gilden's works, a video screen shows a selection of classic noir films. The most important in the group is Jules Dassin's The Naked City (1948), a revolutionary film shot entirely on location in New York City, with the actors interacting with real people. That we can watch this film as we consider Gilden's pictures is suggestive, as this section documents real-but-noir-style people.

Despite the power of Gilden's images, the dialogue between photo and film here is not seamless, for the photos do not appear to be 'noir' as the word is used to describe works made during the 1950s. The characters in Gilden's pictures look somewhat bizarre, closer to, let us say, David Lynch's eerie suspense rather than to traditional mystery movies. Gilden focuses on big eyes, wrinkles and huge glasses, for instance, rather than on the dark, mystery-laden atmosphere. In another example, he shot a man who resembles Orson Welles, but this effect reminds one that, although noir-style films always contain strange characters, they are not the main element.

The Russian Gueorgui Pinkhassov and the French Gilles Peress echo Gilden's mechanics of shooting artists' universes. Pinkhassov pays homage to the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky with photos he took of the artist at home and at work. (These images are in dialogue with video screens showing Tarkovsky's films, including Mirror from 1984). Nostalgia is the theme; a powerful melancholy always marked Tarkovsky's works.

Peress dived into the works of one of the fathers of the nouvelle vague movement, the French master Alain Resnais, by drawing from a collection of photographic location research Peress did in New York and Baghdad for a fictional film yet to be made. This research and the film will serve as a tribute to Resnais' book Repérages (1974), the first book of photographs that Peress ever saw. To access the emptiness that marked Resnais' works, Peress mixed real images from the streets - including one of a hung goat with a mysterious shadow - with fictional computer-generated images.

The Belgian Harry Gruyaert and the French Antoine d'Agata played with more essential film elements and invested in the question of editing. Gruyaert juxtaposed sounds and images of the Italian master Michelangelo Antonioni with some of his own photos projected in a dark room, while d'Agata created the most radical experience - and only filmed work by the participants: the 15-minute short Aka Ana, made in video in 2006 and screened at the exhibit. For this work, d'Agata filmed himself on a trip to Tokyo as a documentary inspired by Empire of the Senses (1976), a highly erotic Japanese film by Nagisa Oshima. Agata's film consists, as well, of pornographic images and treats the body as an object. Yet there is a peculiar look to the eroticism caused by a confusion of bodies and extreme close-ups of sexual intercourse.

The Irish Donovan Wylie and the British Mark Power pursued the notion of the 'innocent eye' with works that come close to installation. Inspired by his early memories of the Irish Catholic-Protestant conflicts, Wylie chose the Elephant from 1989, the last work made by British filmmaker Alan Clarke, who died in 1990. The 39-minute television production solely portrays killings. The lack of explanation for the events is unnerving. Devoid of dialogue, the film camera follows some characters and leads up to a shooting. Surrounding a small room where the film is screened, Wylie hung on the walls photos, newspaper clippings and other objects related to his family. A series of photos he took of a Belfast prison for terrorists can be seen, too: The images of a single cell reveal subtle differences from photo to photo.

Power was impelled by the Polish master Krzysztof Kieslowski's 1979 film Camera buff, which tells the story of a man who discovers the freedom of amateur filmmaking. The film is shown along with images that Power made in the 1970s in Leicester, his hometown, as well as images of his deceased mother. Every image is strongly out of focus and interacts with the Kieslowski screening and also a super-8 film made by Power's father.

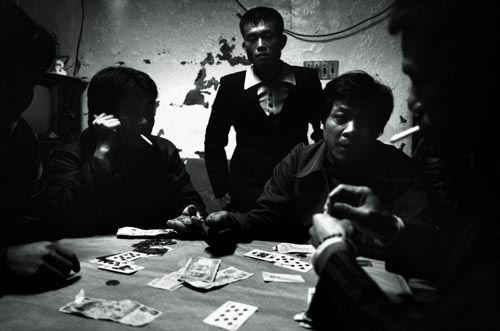

The most impressive works in the exhibit come from the Frenchman Patrick Zachmann's work 'd'après' the Shanghai cinema of the 1930s. In fact, these photos were taken during the eight years that Zachman spent working on a photo-essay on the Chinese Diaspora across the globe, since the end of the 1980s. An intense dialogue between his images and the films produces such a singular effect that viewing them together seems natural and, in fact, a requirement. Zachmann is a prodigiously talented black-and-white photographer and the strongest documentarian of the exhibit. The power of his images comes mainly from his startling notion of mise-en-scène. Zachmann captures more than just beautiful images; he composes real scenes that are masterfully symbolic universes.

'Mise-en-scène' is the key to artistic documentary photography and to Magnum's success. A dialogue between the elements within an image and between elements of separate images and other images creates the real world, even if the 'real' is aesthetically close to the fiction. Magnum's reputation has been built on the dialogue its members have tried to create between art and life, creative expression and documentation, and personal perceptions of universal concerns. 'The Image to Come' celebrates the agency's revolutionary approach and influence, seen most clearly and beautifully in Zachmann's work but evident throughout the exhibit.

A full-colour catalogue accompanies 'L'image d'après: Le cinéma dans l' imaginaire de la photographie' in French and English editions, co-published by Magnum Steidl and Cinémathèque Française, with photographs by the exhibited artists and texts by curators Diane Dufour and Serge Toubiana; Olivier Assayas, Alain Bergala and Matthieu Orléan. For a list of films linked to the exhibit, please visit: www.cinematheque.fr

Alexandre Werneck

Note

1. The exhibition was co-produced with the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB).