The National Gallery, London

23 June-12 September 2004

[image2]

The major loan exhibition of 70 of Russia's best-known and loved 19th century Russian landscape paintings was organised jointly by the Groninger Museum, The Netherlands and the National Gallery, London; in London it was sponsored by BP. Many have never been shown outside of Russia and have not been available even in reproduction. Outside of Russia there are almost no studies of 19th-century art. The West's preference for the avant-garde movement which was shaped in large part by French art and communist Russia's self-imposed cultural isolation, has ensured that little art history of this period has been published in this country.

The Russian art of this period has been strongly influenced by nationalist sentiment, 'Russian artists sought to portray the soul of Mother Russia … Russian Landscape artists wanted to penetrate imaginatively into the very essence of their countryside. For them, painting is a means, not an end in itself, not "art for arts' sake".'2

Objective and dispassionate analyses will take the modern historian so far, but the context of the period is crucial to an understanding of Russian landscape painting; a time of emotive, subjective and fiercely intransigent debate, and the search for a national identity. This was never likely to be a supine or merely decorative genre, but rather an absorbing arena for artistic controversy.3

As the National Gallery's curator of 19th-century paintings, Christopher Riopelle has pointed out, 'Landscape plays a central role in the Russian imagination. The emptiness of the country's vast reaches, the rigours of its climate, the difficulties of transportation, and the intense isolation that long winter months impose, all contribute to a specifically Russian sense of nature, different from - perhaps more fatalistic than - that of elsewhere. In the age of Tolstoy the landscape simply dominated the lives of most Russians.'

Fundamental to all the work in the exhibition is the vast scale of the landscape. David Jackson uses the notion of Motherland as embodied in one of Ivan Turgenev's stories, 'Its ethos, and that of the land, is enmeshed in fierce national pride and lachrymose nostalgia - a place of home, of the Russian soul, a common inheritance - the root of the word filtering into those used for nationhood, the people, birth, parents, mother and father. A vast, overwhelming rural country encompassing huge mountain ranges, immeasurable Steppe, the frozen North and sultry Mediterranean South, giant areas of forestation and expanses of desert - nature, the land, rodina, are concepts which permeate Russian thought, art, literature, music and legend.'4

The exhibition covers the period 1820-1900, which coincides almost exactly with the dates of Leo Tolstoy. In numerous passages of Tolstoy, he writes with a painterly sensibility. In Childhood, Boyhood and Youth, 'Harvesting was in full swing. The brilliant yellow field was bounded on one side only by the bluish forest, which seemed to me then a very distant and mysterious place beyond which either the world came to an end or some uninhabited regions began.'5 Apolitical artists found solace in the landscape when the official policy determining acceptable content in art dominated. Landscape painting found a position above the issues of conservatism and liberalism, traditional and modern. The lack of sociopolitical content meant that various factions could be satisfied, for ideas in landscape were insinuated, not stated. For the most part, the landscape in painting served to create national pride and unity. For Tolstoy's Constantine Levin, '… the country was the background of life - that is to say, the place where one rejoiced, suffered and laboured.'6

The exhibition opens with the founder of Russian landscape painting, Aleksei Gavrilovich Venetsianov (1780-1847) described as '… an outsider in every way'.7 He had a varied career which included initiating Russia's first illustrated satirical magazine (1808), later banned by the authorities. He became an Academician (1811) although he was largely self-taught, yet during the Napoleonic Wars he created political cartoons which ridiculed the French and the Francomania of the Russian aristocracy. In 1819 he left St Petersburgh and settled on a small estate of Safonkovo in the province of Tver. Venetsianov was an inspiring teacher and exerted great influence on 19th-century Russian art, founding a school of realism that eventually encompassed more than 70 artists. He '… painted with a fresh vitality, avoiding academic rhetoric and concentrating on modest scenes of rural Russia … images of ordinary people, the Russian peasantry, at work and rest against a backdrop of agrarian simplicity.'8 Unlike Russian artists who travelled abroad and absorbed the influence of Italian painting in particular, Venetsianov evolved a personal vision of great significance.

In the context of this exhibition Venetsianov's views on art and the respective status of art and literature in Russia at the time are pertinent. 'The art of drawing and painting itself,' he stated, 'are no other than a weapon serving literature and, as a result, the enlightenment of the people'.9 His views supported the dominant view that a hierarchy existed where literature was superior to the visual arts, furthermore, art and literature played a seminal role in the enlightenment of the masses. Literature dominated cultural debate from the 1840s, though by the end of the century there were individuals who sought to redress the position. Landscape was outwith the constraints imposed on history or genre paintings, '… a landscape pure and simple, is by its very nature anti-literary. It doesn't tell a story; its subject is nature and not society, its aim is to arouse feelings and summon up reactions, not to promote political attitudes.'10 That landscape painting developed so strongly and independently of the critical infrastructure of the Academy is itself a most interesting phenomenon.

Artists paid lip service to literature, for example, Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin's, (1832-1898) 'In the Wild North' (1891) takes the opening line of a poem by Mikhail Lermontov as its title. The first whole room of the exhibition is devoted to the work of Shishkin, whose work presented farm labourers, the noble peasant with whom Tolstoy so identified, as the symbol of honest purity. Their relationship with nature was central to their integrity. Shishkin achieves this by a liberating sense of space achieved in visual terms by lowering the horizon line. His paintings become a song of praise to Mother Russia - the human presence is insignificant against the vastness of nature. The sheer scale of his paintings ensures monumentality in spiritual terms.

The exhibition includes work by 15 artists dating from 1820 to the early years of the 20th century. Three rooms are devoted to the most important artists of the age - Shishkin, Arkhip Ivanovich Kuindzhi (1842-1910) and Isaak Ilich Levitan (1860-1900) - allowing viewers to observe the individual achievements of these artists. The first room shows the work of Shishkin whose work combines panoramic vision with meticulous attention to detail. Shishkin's etchings constitute an important aspect of his legacy; he became the foremost engraver of the second half of the 19th century and was instrumental in reviving the tradition of etching in Russia. Like Shishkin, Kuindzhi's painting was informed by his trips to France, Germany, England, Switzerland and Austria in the 1870s. Kuindzhi's landscapes are characterised by their panoramic vision. His use of colour is expressive. 'There is nothing in European art to compare to Kuindzhi's landscape paintings,'11 claims Henk van Os, in his catalogue essay, claiming that Kuindzhi blazed his own trail to find the heart of Russian nature. Where Shishkin was described as the 'accountant of leaves' for his exact attention to detail, Kuindzhi's melancholic, lonely landscapes are almost abstract.

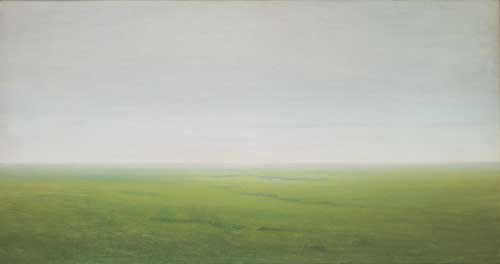

Isaak Levitan was the artist that Chekhov so greatly admired, believing that the Russians took landscape painting more seriously than the French, yet it is possible to see in Levitan's work the influence of Corot and Monet. Levitan described space in a completely different manner to his contemporaries. His paintings consist of three overlapping bands of colour, painted with a broad brushstroke. He creates an absolute sense of space, an unforgettable picture of the Russian landscape. 'This is no landscape icon, but certainly an iconic painting of nature.'12 The difference between these three seminal artists illustrates the vast range in Russian landscape painting, especially of the second half of the 19th century.

By the 1860s an emancipating process had taken place for artists with regard to the role of the Imperial Academy of Arts. In a broader context, great changes took place in Russia that would have ramifications in cultural terms. The emancipation of the serfs in 1861, and other reforms aimed at tackling the crippling social divisions were undertaken by Alexandr II. In 1863 a group of 14 artists had refused to paint the set subject in order to attain the Grand Gold Medal. They formed an artists' co-operative in order to gain independence. This was an important development in the subsequent formation of the 'Wanderers', who from 1870 organised travelling exhibitions and sought artistic freedom from the constraints of the Academy. One of the founder members was Aleksei Savrasov, an influential teacher at the Moscow School of Art who travelled extensively studying from nature. He has been described as the founder of the 'mood landscape'.

These developments were driven by the desire to challenge the supremacy of history painting. Painting from nature in the landscape was low in the Academy's hierarchy, for it supported no social cause, yet in other parts of Europe landscape painting had acquired a higher status. Shishkin had studied in Düsseldorf with Andreas (1815-1910) and Oswald Achenbach (1827-1905). Their work was well known and honoured in Russia and their influence was felt all over the world. 'The representation of reality, extreme precision and romantic overtones: this mixture was Andreas Achenbach's secret menu for success. Painting in this way he interpreted the traditions of landscape art - including that of the Barbizon School for the bourgeoisie of central Europe.'13

The influence of the Düsseldorf landscape tradition of this period and the teaching there, can also be found in Australian and American landscape painting. Indeed, 'Russian Landscape in the Age of Tolstoy' resonates with the sense of awe and discovery that one finds in the painting in Australia that addressed the phenomena of discovering and recording the new frontiers of a strange and sometimes menacing landscape. The influence of European art on Russian art was immense, for there was easy access to painting in exhibitions and reproductions. Russian collectors bought work by contemporary Dutch, French and German artists.

The paintings of Mikhail Nesterov conclude the remarkable exhibition of Russian landscape paintings. Perhaps the finest painting of his on show is

'St Sergius of Radonezh' (1899). The relationship between the figure and the landscape is first exemplified in the work of Venetsianov whose painting shows the emotional link between individual and landscape in Russian culture. Nesterov defined his work as 'poeticised realism'. His works are heavily steeped in the Christian spiritual tradition, and seek to define man's search for the meaning of his existence through God, in the context of the natural world filled with silence and tranquillity. In this country the work of the Pre-Raphaelites was created within a similar ethos. Nesterov created church murals in Kiev, Abastumani in Georgia and Moscow. His portraiture was also significant.

Social change was so profound in 19th-century Russia that it is not in the least surprising that painting of the same period can be seen to have absorbed the complex and paradoxical cultural ramifications of such change. Intellectually this exhibition is a remarkable and demanding experience. The accompanying catalogue with scholarly essays challenge so many notions we have of Russian art, and in doing so demand that one comes to grip with the literary and political history of Russia. Nationalism grew in all parts of Europe in the 19th century but in Russia the critics of the Tsarist regime monopolised nationalist thought. Their aim was to define a way of life in contrast to what they perceived as the imperial, ideologically corrupt values, based on those of the West, introduced by Peter the Great. A typically Russian experience could, perhaps ironically, be found in landscape, hitherto an apolitical genre. In Slaves of Literature: Literature, Visual Art and Landscape Art, Sjeng Scheijen sums up the central issues of this superb exhibition with great poignancy:

People were quite ready to admit that the Russian landscape was bare, barren and inimical yet saw in these very things the tokens of an extraordinary spiritual wealth. Deep in the Russian consciousness lies the conviction that this forbidding climate, the poverty of the soil, the social violence, the lack of human rights, the coarseness and the alcoholism - in themselves repugnant are in fact the well-spring of the resilience, energy and spirituality of the Russian people. This mythical paradox, that Christopher Ely describes as outer gloom and inner glory, is one of the recurring motifs throughout Russian culture, finding in landscape art its own particular and monumental representation.14

References

1. Camilla Gray. The Great Experiment in Art: Russian Art, 1863-1922. London: Thames and Hudson, 1962.

2. Henk Van Os. Russian landscapes: a première. In: Jackson D, Wageman P (eds). Russian Landscape. Groninger: Groninger Museum/London: National Gallery, 2004, 16-17.

3. David Jackson. The Motherland: tradition and innovation in Russian landscape painting. Ibid, p.53.

4. Ibid, p.53.

5. Leo Tolstoy. Childhood, Boyhood and Youth (translated by Rosemary Edmonds). London: Penguin Classics, 1964, p.32.

6. Leo Tolstoy. Anna Karenina (translated by Rosemary Edmonds). London: Penguin Classics, 1978, p.257.

7. Henk Van Os, op.cit, p.17.

8. Jackson, op.cit, p.53

9. Quoted by Sjeng Scheijen. Slaves of Literature: Literature, Visual Art and Landscape Art. Ibid, p.89.

10. Ibid, p.89.

11. Henk Van Os, op.cit, p.35.

12. Ibid, p.38.

13. Ibid, p.21.

14. Scheijen, op.cit, p.101.