Chisenhale Gallery, London

3 July – 30 August 2015

by HARRY THORNE

Solar deities and the act of sun worship are the stuff of legend: the Aztec people performed human sacrifices to prevent the sun god Tonatiuh from halting his journey through the sky; in Chinese mythology there were originally 10 suns – all brothers – nine of which were shot down by a hero with a bow and arrow; Ancient Egyptians worshipped the solar deity Ra, whose eye was the sun and whose daughter was a lioness. If you explore this subject further, you will discover more names and even more fantasy, but beneath each interpretation a single principle will remain unchanged: respect that which gives life, which dictates, and which shows mercy. It may be the stuff of legend, but when stripped back to its rudiments, it doesn’t sound too unfamiliar.

In Ancient Lights, his latest exhibition at London’s Chisenhale Gallery, Australian artist Nicholas Mangan (b1979) applies a modern filter to this archaic principle, presenting, via two video works, a 21st-century ode to – and borderline worship of – the sun. Mangan has a vested interest in humanity’s appropriation of the natural for unnatural needs. In 2009-10, he crafted a coffee table out of coral rock; in 2012, for A World Undone, he examined Zircon, a 4,400-million-year-old mineral found in the Earth’s crust; and, in 2013, his project Progress in Action reflected on the 1989 civil war on the pacific island of Bougainville, a conflict largely born out of disputes over land use and ownership.

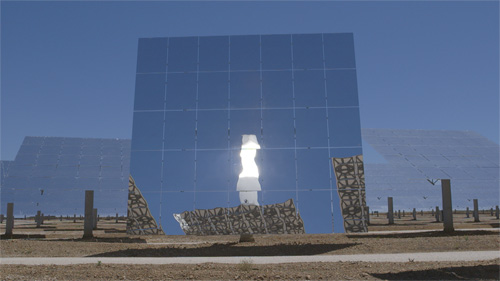

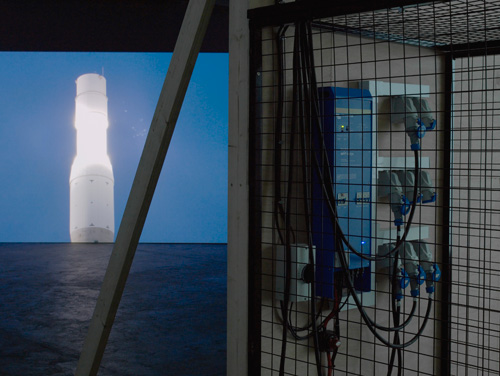

While human subjects are absent from Ancient Lights, human influence abounds, with the film in the farthest room documenting a series of occasions at which man and the force of the sun intersect. It skips from the concentric mirrors of the Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant in southern Spain and a flickering Siemens pressure transmitter to audiovisual documentation of sunspots gathered by Nasa and several rotating dendrochronological samples collected at the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research in Arizona. The content may be expansive and heterogeneous, but the film is direct in its situating of the sun at the centre of a series of cyclical systems, both geophysical and cultural. To the sound of a pulsating mechanical drone, the video unites this crowd of disparate concepts through a simple indication that they are all desperately reliant on the same source.

On the wall of an adjacent room is a projection of a Mexican 10-peso coin, spinning in slow motion and refusing to fall. The work is something of a sculptural vignette of the first film – the perpetual motion of the coin echoing the sun’s thermodynamic equilibrium – but the significance of the 10-peso piece goes beyond summary alone. On one of its silver sides, the coin depicts the Aztec sunstone, a relic that was central to the Mesoamerican people’s belief that sacrifice was necessary to a continuation of human life. While we have moved beyond barbarism, for Mangan, the contemporary relationship that we continue to enter into with the sun echoes that which came before, in that it is entirely based on speculation and risk. “If you want energy, you have to pay for it,” he says. “There has to be a loss. At the moment we have batteries full of sun, but those batteries are going to drain out, there’s not an infinite bank.” Every time we make use of the sun’s energy, we offer a little something of ourselves in return. We give something of our reality – money, and therefore labour, and therefore time – over to that burning, solar overlord. While we may steer clear of human sacrifice, we are still complicit in the act of “offering”.

Visually, Ancient Lights is a captivating project, and the two films are astutely balanced. With one attending to the macro and one to the micro, the projections work as well individually as they do as a pair, creating a united exhibition that is capable of attending to many different aspects of society. But while it may be bound up in an artwork, Mangan is intent on illustrating how these particular ruminations on the concept of the Anthropocene directly apply to a reality that transcends the art world. In order to reify the fundamental principle that sits behind Ancient Lights, this entire exhibition is powered by solar panels placed on the roof of the gallery. It is a literal channelling and redistribution of light, and, therefore, without the sun, there would be no spinning coin or Ancient Lights, just as, without the sun, there would be no gallery, no infrastructure, no weather, no economy, no civilisation.

By definition, the sun still resembles that formless being that we have come to demarcate as a god. Our veneration may be somewhat less intense than that of the Aztecs, and our understanding of its structural composition far more advanced than that of the Ancient Egyptians, but it is undeniable that the energy the sun emits continues to play an imperative role in the existence of contemporary civilisation. While inanimate, the sun gives life and it grants sight, it protects, it allows for growth, it dictates the climate and the weather, and it choreographs the day and the night. It gives all of this and, perhaps most god-like of all, it never receives. If that act can no longer be met with worship, then surely at the very least it should be treated with respect.