Courtauld Gallery, London

12 September – 14 December 2014

by ANNA McNAY

This small but hugely powerful exhibition of work by Jasper Johns (b1930) is the second in the Courtauld’s new series of shows by contemporary artists who speak to a longer history of art. The 10 works selected might be seen not only to summarise the oeuvre of Johns himself, demonstrating many of his known methods and stylistic marks, but also to tell a wider story of art and artists, their processes and interactions, and, more broadly, a prescient – and Old Masterly – tale of life and death.

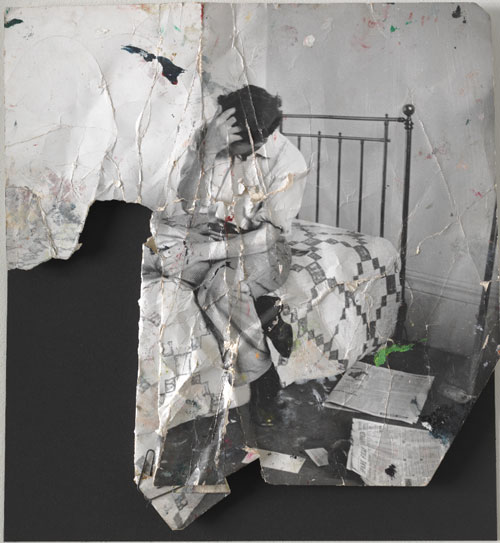

In the early summer of 2012, Johns was sent a Christie’s auction catalogue for the sale of Francis Bacon’s Study for Self-Portrait (1964). In it was a full-page reproduction of a photograph by John Deakin, showing Lucian Freud posing on a cheap bedstead in Bacon’s studio. Bacon had, unusually, used this photograph as the starting point for his self-portrait. Johns became entranced by the image, which, in its reproduced form, had heavy black areas where Bacon had folded and torn the original, and where the copiers had placed the damaged original on a backing sheet, and thick, wiggly lines, where he had creased it. For the next 18 months, Johns worked solely with this image, creating and recreating numerous versions in pencil, pastel, watercolour, charcoal, ink on mylar, oil on canvas and etchings with numerous state proofs. All but the etchings are on display here.

Johns has often worked from found objects and images to create his repetitive and exploratory series, but never has he been so caught up with one solitary image, and never before has this image had such a backstory of its own. For here, we have an artist working from an image of an artist, taken by an artist (for Deakin surely deserves this title, too), and used by another artist as a stand-in for an image of himself, superimposed with his own features.

To begin with, Johns made a photocopy of a tracing of the reproduced photograph. He then broke this down into segments, like a patchwork, colouring them as a child would a colouring book, with no two neighbouring fields the same colour. He also worked in monochrome, using grisaille watercolours, animating the works with the odd block of colour, pulling out shapes. These early sketches encapsulate Johns’ way of working, getting to know and understand the details of his source material, trying out different colours, marks and media.

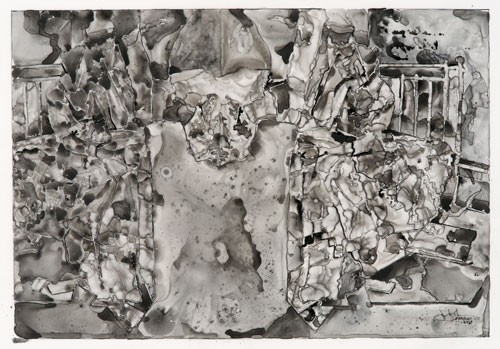

Then something amazing happened. Johns fixed the photocopy on to the right-hand side of a larger sheet of paper and created a mirror image of it to the left. Where the two drawings met, a new shape emerged in the centre: that of a skull. Its appearance was complete happenstance – like with a Rorschach inkblot test – and despite Johns having deliberately introduced skulls into some of his previous works, the mind – if not the hand – of the artist was completely absent on this occasion. The figure of Freud sitting on the bed was now also doubled, looking inwards, contemplating this huge memento mori. The black area, from Bacon’s tears, became a pedestal supporting the weight of the skull.

Now Johns was even more devoted to working on this image than ever. He went on to produce his larger pieces, mainly monochrome, with patches of colour being added to draw out certain aspects and embellish the overall composition. With the large oil on canvas, Regrets (2013), for example, Johns struggled for a long time to work out how to finish it. Originally, it was painted in bright colours, which he later shrouded with darker tones. He then abraded the surface with sandpaper so that flecks of the underlying colours were revealed. Still dissatisfied, he went on to pick out segments of the right-hand figure, colour coding with primary reds, blues and yellows, creating echoes of the image beneath, but also new visions on top, including the yellow “hand” on Freud’s face, which now appears to be a face in its own right. With the criss-cross markings – typical of Johns – on the skull, this remains a prominent feature of the work: death looming, a warning to us all. And with the two figures, seated at the left and right-hand of this “God”, the idea of impending judgment – of the separation of good from evil – cannot be overlooked.

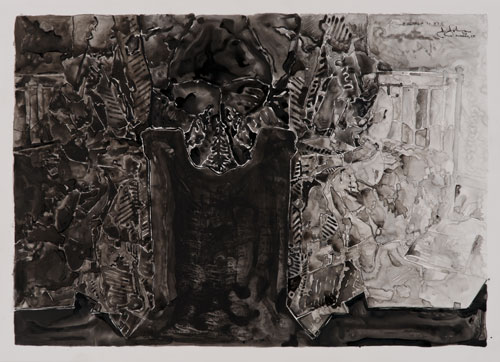

In Johns’ ink on mylar drawings, the skull becomes even more menacing, dark and imposing, sitting on the shrouded altar. There is a contradiction here between the absence and presence of the artist – with the ink behaving almost independently, pooling and drying to remove any obvious trace of the pen and brush marks, but the crosshatching and segmenting so very obviously trademarks of Johns. There is an added effect, which, in a way, completes the artistic circle, of these images appearing almost photographic, like negatives from a damaged film cell. This, of course, relates them back to Deakin’s original photograph – which, it is worth bearing in mind, Johns never actually saw.

All the works are finished with a stamp – or reproduction of a stamp – reading “Regrets, Jasper Johns”. The artist found this rubber stamp lying by his photocopier. It dated from two or three years previously and was formerly used to answer all unwanted mail he received. Whether the expression, which became the title of the series, has any particular significance for the artist, especially in conjunction with the skull and meditation on the themes of mortality, remains unanswered. Johns is notoriously evasive when it comes to questions on the subject of his works. He pours so much energy into creating them that, once finished, he claims to have none left for talking about them – their theme is fully exorcised. This is of no great detriment to the viewer in this instance, however, since the works in this series speak loudly and clearly for themselves.