Leila Heller Gallery, New York

5 September – 5 October 2013

by JILL SPALDING

The time away has served Deitch well. His return has been heralded with the equivalent of trumpets and the show that marked his re-entry to the Manhattan art scene upstaged even New York fashion week for its glamour and buzz. The jumble and crush of the crowds surging into the gallery, and the show’s crazy-quilt hanging and quirky juxtapositions, evoked a sale of donated material for a celebrity charity until I was finally able to carve out enough space to look at the work.

A first viewing scrambles the brain. Hastily put together over the summer (to replace a show, I was told, that has been postponed to November) but gestating for the 30 years since Deitch’s first show on the subject, the works arc from the 1940s to the present. Some are for sale, others not; some vibrate off their frames, some disappear into them; and the mediums range from paint on aluminum, to ink on handmade paper, to ink on linen, to acrylic on wood, to casein on canvas, to printing on Diasec, to permanent marker on Plexiglass, to poured glass, to bronze, to watercolor on vellum. There is even the painting-on-concrete that made walls the first home of tagging.

Comments rippled through the crush like verbal graffiti: “The trouble with group shows is that you can throw in anything you like”; “Collectors of Dubuffet wouldn’t want to see him hanged in with everything else; “Great names, weak material”; “Great fun, though not to be taken seriously”. But those who paused to look were hooked.

Ironically, as with the great Pop happenings of the 1960s and the frenzied openings of the 80s, the vibe of spike heels, punked-up hair and an actress in a body stocking raked with lettering, spoke to a moment to be taken quite seriously. The eye-opening conceit of graffiti as stream-of-consciousness calligraphy, and the east-meets-west traditions of writing as art that are revealed by their seemingly ad hoc juxtaposition prove unexpectedly thought-provoking and discerning. Deitch’s subtext – graffiti as an art form – is equally meaningful, indeed poignant, given that his controversial show for MOCA, which championed that very point, had speeded his exit.

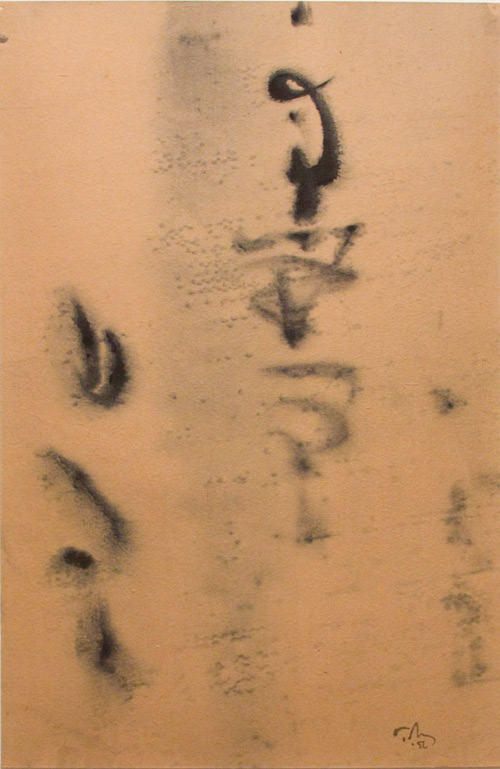

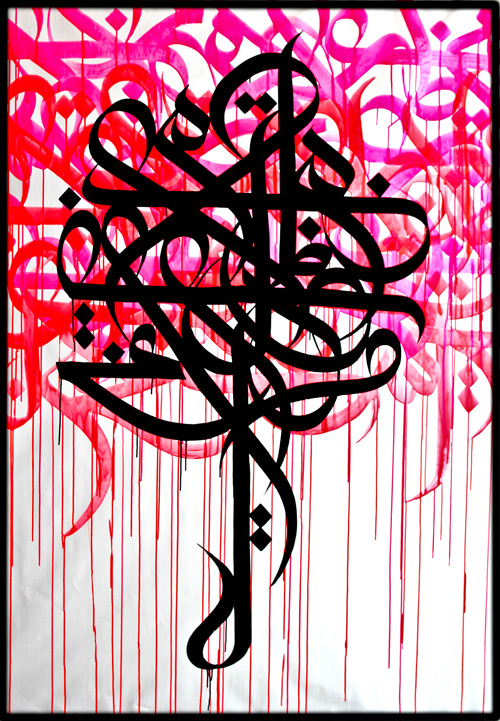

Commenting in the gallery’s excellent catalogue on the power of the letter, and on the drawing gesture and brushstroke as a basis for art-making, Deitch expands on his revelation about the link between calligraphy and graffiti which had informed his pioneering show of 1984; namely how both New York’s 60s street artists, who had been styling their tags into vivid abstract symbols, and a group of Persian artists who had begun whirling traditional calligraphy into pulsing abstractions, had played off Abstract Expressionist signage, Pop Art and even Chinese and Japanese calligraphy to contribute significantly to the Modernist vocabulary.

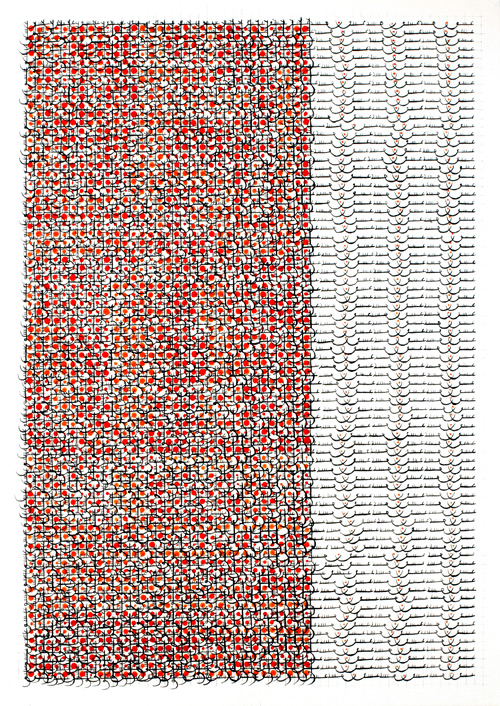

That the resultant “calligraffiti” warrants a new show is evidenced by its impact on a new generation of artists and the importance of its imagery in defining the Arab spring. Leila Taghinia-Milani Heller’s essay tracks the power of the letter from the time of illuminated manuscripts and recounts how the chance methods of the Dadaists, the signage of the Surrealists, the hypergraphic systems of the French Letterists, and the street signatures that New York artists were drawing from cartoons and sci-fi, together formed a visual language that was taken up all over the world. Concurrently, in Iran, Hossein Zenderoudi had founded a school of painting, Sagha Khaneh, whose explorations had ripped open the door for what proved a shocking manipulation of calligraphy – the tradition revered for centuries in Judaic and Arab and Islamic societies – into swirling images of notions that were overtly subversive

Among the new-to-us names are revelations underscoring how little we have bothered to concern ourselves with the Middle East’s investigations: the energy of Mohammad Ehsai’s whooshed insignia; the cool intelligence of Reza Mafi’s op-art inflected symbology. Among the familiar, there are comforts and delights: Lee Krasner holds up brilliantly against Jackson Pollock; Pat Steir’s late-career evocation of ink-scroll calligraphy ravishes. There are absurdities, such as a small Basquiat scribble priced at $295,000 versus a strong Baziotes oil painting at $75,000. And surprises; the Mark Tobey, albeit minor, apprises of his longtime fascination with lettering. There are curious omissions – a nod to Dali or Miró would be welcome. And where is Ed Ruscha? The gallerist I asked said that they don’t consider his work calligraphy, but it may be pertinent that he was one of the artists who famously resigned from the Museum of Contemporary Art’s board to protest Deitch’s restructuring.

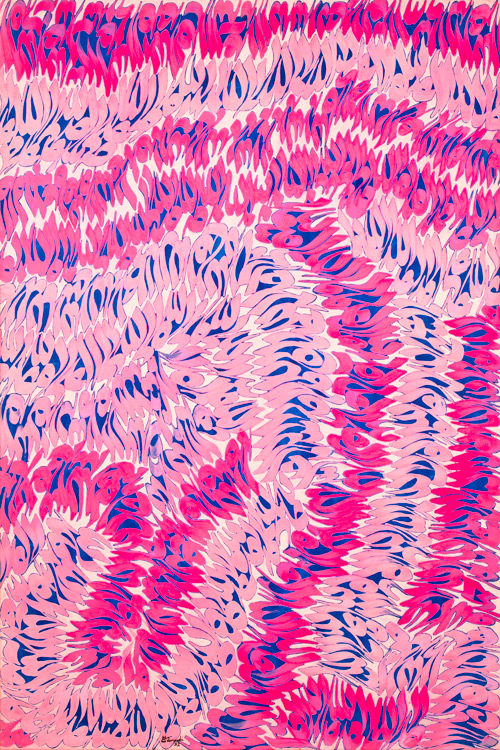

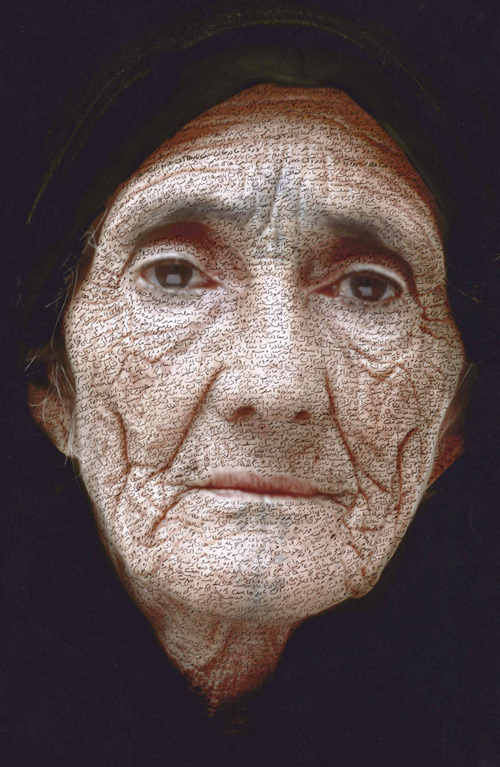

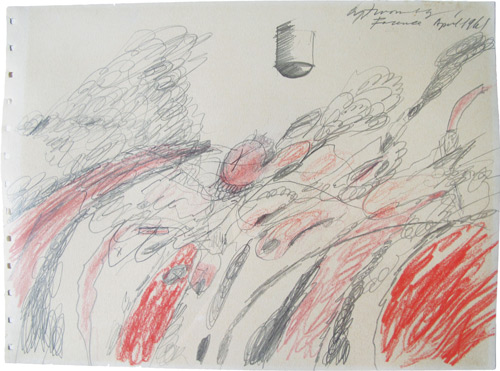

My only cavil is with the overall quality: though arguably irrelevant to Deitch’s message, it grates that a minor Twombly pales beside a powerful ROSTARR. On the other hand, given the speed with which the show was put together, the sweep is impressive. North Africa dazzles and, despite US sanctions against Iran that prevent loans of its art, the Persian artists hold their own – indeed, in instances that might be laid at the door of haste or the reluctance of collectors to loan hugely valuable work, overshadow their western counterparts. Muna Rihani al-Nasser, who chairs the UN’s Women for Peace, pointed her friends toward the “pink painting” by Zenderoudi, and the “urn” by Farhad Moshiri, both “bargains” and “great investments” at $400,000 and $150,000 respectively: Layla Dibah, who co-curated the current Iran Modern show at Asia Society Museum, said she has been tracking the Zenderoudi for years. Several of the artists were present; Pouran Jinchi, whose solo show, The Blind Owl, at The Third Line in Dubai, 18 September – 24 October 2013, explores calligraphy through the lens of a masterpiece by the Iranian writer Sadegh Hedayat; Hadieh Shafie, one of the Iranian artists working here; the French Tunisian graffiti street artist eL Seed, whose work, now on canvas, had been conspicuously pre-sold (possibly because, in the supreme irony of success, he has been hired by the Qatari government to paint a series of tunnels), and the graffiti star Ayad Alkadhi, who was arranging for admirers of his drawings to be photographed in front of them. Shirin Neshat electrified by her presence: joining the fans who lined up to shake her hand, I asked if she liked how her stacked portraits of a man and a woman were presented – her answer underscored her cult following: “Oh yes, but I would have put the woman on top.”

It is interesting to compare Calligraffiti with the compelling exhibition of Iranian modernism now on view at Asia Society Museum. But see this show first. It will give you instant instruction in the new universal language, the visual Esperanto, that the larger show incorporates more subtly, but with less energy and freshness.